Understanding Cultures: Hofstede's Framework

This article is mainly based on the research paper by Geert Hofstede "Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context" (2010).

A Perspective on Culture

As scholar Geert Hofstede puts it, "Culture is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others". Differently from personality factors, culture is a collective concept. It stems from sociology, and is present in groups, which Hofstede delineates as Nations in his definition of dimensions which can help put a framework around the concept of culture. There is no culture without a group of people sharing common values, beliefs, customs, social context. At the same time, culture is a general concept, which is subject to individual variation based on personality factors of people. As Hofstede writes in the paper, "... culture and personality are linked but the link is statistical; there is a wide variety of individual personalities within each national culture, and national culture scores should not be used for stereotyping individuals."

Culture in International Business

In the domains of international marketing and business, culture is a pivotal factor to account for. Not only because of variations in tastes and habits, but especially due to the different consumer behavior tendencies which can be noticed in different cultural contexts. These consumer behaviors must be carefully considered whenever crafting and delivering a cross-cultural business strategy, if one intends to maximize chance of success. Very often, accounting for cultural variation may correspond to using an adaptation strategy of marketing, in which a company molds its strategy around the cultural context it operates in. This is glocalization: thinking globally, acting locally. HSBC is a common example of strategically adapting to different cultures, while maintaining a clear brand identity across nations (although the bank has apparently pivoted away from their "World's local bank" slogan).

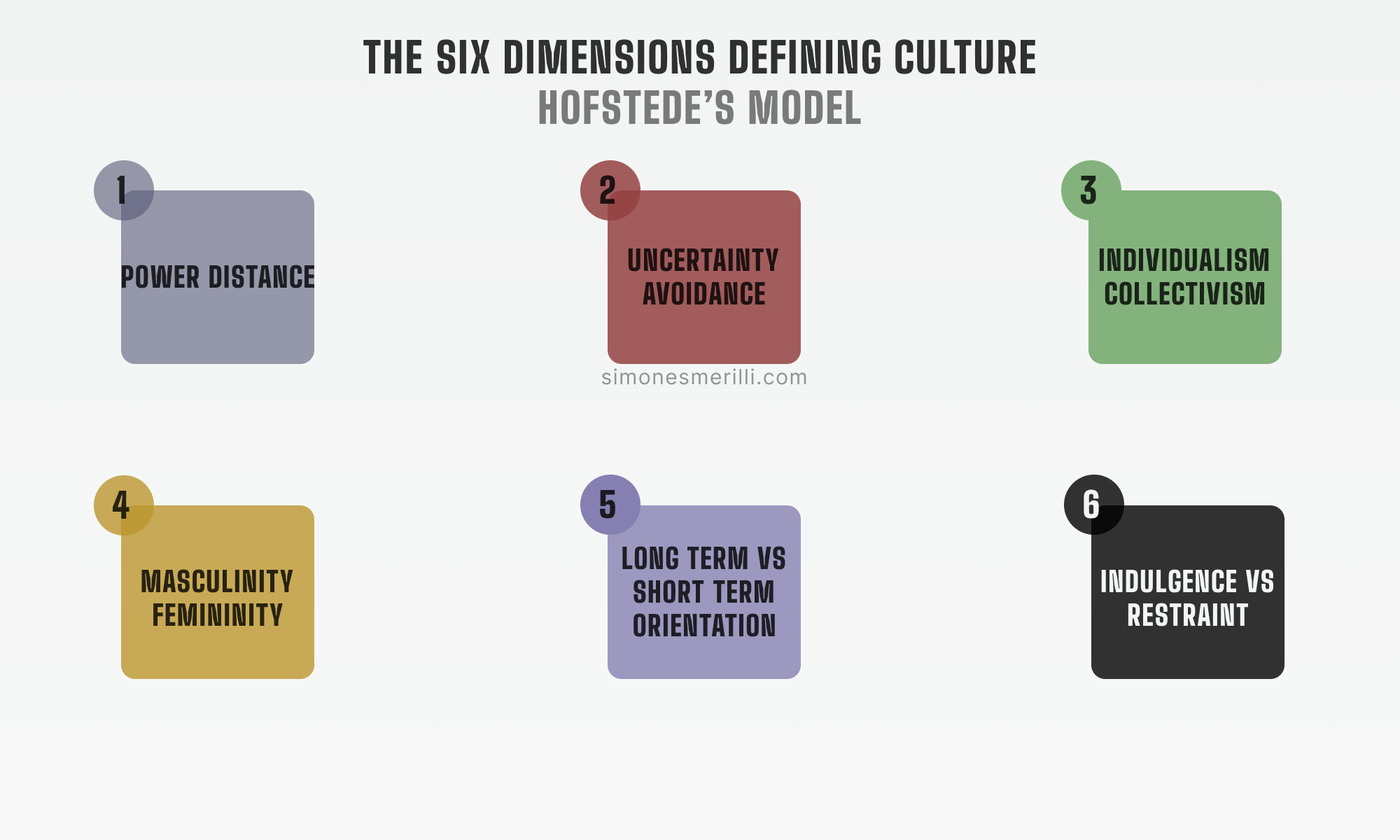

A Model for Defining Culture: Hofstede's Six Dimensions

By analyzing a large database of surveys of "more than 100000" (Hofstede, 2010) IBM employees in the 1980s, Geert Hofstede began to notice some common patterns, identifiable dimensions which appeared to be correlated with specific cultures and Countries. "A dimension is an aspect of a culture that can be measured relative to other cultures" (Hofstede, 2010). Hofstede originally developed a framework composed of 4 dimensions for defining culture. The model has then introduced two additional characteristics in later years, as research on the topic of culture expanded (Hofstede, 2010). In order to evaluate a culture, scores from 0 to 100 are assigned to each dimension, which, therefore, can be imagined as a spectrum. The six cultural dimensions are:

Power distance

All societies are unequal, but some more than others. Power distance is "the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. This represents inequality (more versus less), but defined from below, not from above" (Hofstede, 2010). This dimension plays on the fact that the degree of societal inequality varies among Countries and cultures, while all societies are unequal to some degree. Power distance can be defined as small or large. As Hofstede illustrates in his paper, in small power distance societies, for example, children are treated equally by parents. At the opposite end of the spectrum (large power distance), parents firmly teach children (and value) obedience.

Uncertainty avoidance

This is the level of stress in a society in the face of an unknown future. "It indicates to what extent a culture programs its members to feel either uncomfortable or comfortable in unstructured situations" (Hofstede, 2010). Uncertainty avoiding cultures try to minimize the chance for unstructured situations by setting up strict rules, regulations, beliefs. In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, the unknown is seen as an enemy to avoid at all costs. "Uncertainty avoidance deals with a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity" (Hofstede, 2010). This dimension is different from risk avoidance, as Hofstede points out in the paper. To make two opposing examples, in low uncertainty avoidance cultures each day is taken as it comes, as the inherent uncertainty of life is embedded in people's way of being; on the other hand, in strong uncertainty avoidance cultures there tends to be high level of neuroticism, emotional reaction, stress.

Individualism — Collectivism

This dimension analyzes the degree to which people in a society are integrated into groups. In collectivist cultures people are engrained in in-group vs out-group thinking and embedded into groups ever since they are born. Collectivist cultures think in terms of we. At the opposite end of the spectrum there is individualism, in which I is given more importance than we. The individual is considered the most relevant element of society, and there is no strong sense of belonging to groups. "Individualism does not mean egoism. It means that individual choices and decisions are expected. Collectivism does not mean closeness. It means that one "knows one's place" in life, which is determined socially" (Hofstede, 2010). In individualistic cultures, "speaking one's mind" is considered necessary, as opposed to the collectivist cultures emphasis on maintaining harmony and loyalty by being excessively agreeable if necessary.

Masculinity — Femininity

This dimension looks at the division of emotional roles between women and men. This is "the distribution of values between the genders which is another fundamental issue for any society, to which a range of solutions can be found" (Hofstede, 2010). Taboos are present in high masculinity cultures, in which the mere fact that a taboo exists reinforces the presence of the characteristic. "Masculinity is the extent to which the use of force is endorsed socially", Hofstede writes. Masculinity is mostly characterized by assertiveness. Femininity is driven by care and a high value placed on emotions. As an example, high masculinity cultures present a bias toward believing that "work prevails over family". In contrast, high femininity Countries emphasize the importance of having balance between work and personal life. According to Hofstede's research, masculinity is high in Countries such as Japan and Italy, while low in the Nordic Nations (e.g. Norway, Denmark).

Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation

Long term vs short term orientation was added later in the framework (Hofstede & Bond, 1988), and is a concept which stems from Confucianism. It refers to the choice of focus for people's efforts: the future or the present and past. While in short term oriented cultures there is a deep focus on what happened in the past or in the present, this is not the case for long term oriented cultures, which rather believe the future is what matters most. Traditions are key in short term oriented cultures, whereas flexibility and adaptation is at the core of long term societies. "In a long-time-oriented culture, the basic notion about the world is that it is in flux, and preparing for the future is always needed. In a short-time-oriented culture, the world is essentially as it was created, so that the past provides a moral compass, and adhering to it is morally good" (Hofstede, 2010). In short-term-oriented cultures, "traditions are sacrosanct". Traditions are, instead, adaptable to changed circumstances in long-term-oriented cultures.

Indulgence versus Restraint

The last dimension in Hofstede's model is indulgence versus restraint. This is a relatively new element, which entered the framework in 2010, thanks to the work of Minkov (Hofstede et al., 2010). "Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that controls gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms" (Hofstede, 2010). In indulgent cultures, there tends to be a higher percentage of obese people if food is abundant, compared to restrained Countries.

Hofstede's Six Dimensions model is not set in stone. Scholar Brendan McSweeney put forward a comprehensive critique of it in this 2002 paper. With that being said, the framework can provide an anchor point for understanding cultures at a deeper-than-surface level, free from bias and aware that personality traits vary widely among individuals, even if part of the same cultural background. This, in turn, can be a source of competitive advantage for carrying out examined international business and marketing strategies with a holistic view of consumer behavior and characteristics.

I also write a weekly newsletter. If you enjoyed this post, consider signing up here, to stay up to date with new posts and receive thought-provoking ideas once a week.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context.

McSweeney B. (2002). Critique of Hofstede's Culture Model

—

SIMILAR POSTS