Leadership in Organizational Change | Part 1 | Leadership

Organizational Purpose

Every organization aims at creating value for the outside world to capture. Business, and any organizational endeavor, is a cooperative game of value creation and capturing (http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~hstuart/VBBS.pdf), as Brandenburger and Stuart postulate in their 1996 paper titled "Value Based Business Strategy". Cooperative game theory provides a framework for depicting how value is delivered and appropriated by organizations and their networks of suppliers, partners, buyers, competitors. The concept of value is often confused and lacks a proper agreed-upon definition in the business environment. As a matter of fact, the meaning of value can vary based on the context in which it is brought up, as well as individual mental models. To explore the definition of value in an organizational context provided by scientific literature, we need to begin from Michael Porter (1980), inventor of the "5 Forces Model of Industry Analysis", and the "Competitive Positioning framework" of strategic management. According to Porter, value is created by the vertical chain of players as a whole (suppliers, firms, buyers). Each player provides and captures monetary and non-monetary value in the process of carrying out their activities. To understand further how value is divided among the players of the chain, Brandenburger and Stuart developed and put forth the concept of "added value". "This is defined as the value created by all the players in the vertical chain minus the value created by all the players except the one in question." (Brandenburger & Stuart, 1996).

Organizations, at their core, are made, run, composed of people. To create and maximize value added, organizations need appropriate structures and human connections that keep a balanced approach to doing business while remaining aware of how their activity impacts the surrounding environment and people. As James Carse points out in his book "Finite and Infinite Games", organizations can adopt an infinite mindset, in which long-term thinking is at the center of everything the business does, and the way it acts. An infinite mindset corresponds to being aware that there is abundance in the game of business, as opposed to scarcity. According to this line of thought, infinite-minded organizations are interested in cooperation, relationships, and look at the long term effects of their actions, as opposed to being stuck in aggressive competition in the present.

Those who play the infinite game place value on the people component of every organization. They are aware that building trusting teams and creating a culture where the human being is considered pivotal are crucial aspects in order to win over the long term. To create a humanistic environment, these organizations are conscious of the relevance of authentic leadership; leadership which provides a meaningful direction. However, in order for leadership to be meaningful, there is the need of appropriate and effective leaders. The domain of leadership is a widely studied one, and its development has been exponential over the last two decades, when a call for emotionally-intelligent leadership (Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence) has started to become widespread and agreed upon in the organizational and business environment. Although many leadership theories and frameworks have been developed over the decades, there seem to be some common behavioral and psychological patterns which can be identified in great leaders.

Defining Leadership

As W.C.H Prentice asserts in his 1961 article "Understanding Leadership", leadership is "the accomplishment of a goal through the direction of human assistants." And this definition is one of the reasons for which Prentice calls for a democratic approach to leadership, in which the individual and their personal characteristics are taken into account thoroughly. It is only by implementing a style which is based on authentic human relationships that "the accomplishment of a goal through the direction of human assistants" can be achieved. Besides the key relevance which is given to human assistance in Prentice's definition of leadership, there is also a heavy focus on the accomplishment of a goal. This provides us with an additional insight into the role of establishing a clear direction in leadership. The work of Prentice is ahead of its time, and lays the foundations for the more recent developments of leadership from authors such as Daniel Goleman and Abraham Zaleznik.

Donnelly, Gibson and Ivacevich (1992, p. 407) give such a definition of leadership: “leadership is the ability to persuade others to seek defined objectives enthusiastically”. We can notice how the people factor is always present in leadership. Leadership exists only with the consensus of followers. There is no leader without a greater vision that is shared by a group of individuals aiming at the same direction. And the leader is the individual providing the direction to a group or organization. In order to provide a direction to the group, a leader needs, therefore, to communicate clear values, intentions, and a vision. For this reason, leadership has an impact on people's lives, whether directly or indirectly (Bennis, 2007).

These are characteristics that can be developed over time, especially as people experience challenges and difficult events in their lives. It's what Bennis and Thomas call crucibles, in their article "Crucibles of Leadership" (2002). Crucibles are severe, intense, often traumatic life tests or trials most of us face during our existence. And in the authors' point of view, it is exactly crucibles that shape leaders. "Everyone is tested by life, but only a few extract strength and wisdom from their most trying experiences. They're the ones we call leaders" (Bennis & Thomas, 2002). For this reason, following this view, leaders possess the unique characteristic of "adaptive capacity": the ability to emerge stronger than before from adversity.

Although the main definition of leadership has not varied significantly over time since its inception, there has been a wide evolution of the concept, approaches, styles, qualities related to leadership. One of the first definitions of leadership can be traced back to The Art of War (500 B.C), the must-read book by Sun Tzu for every military leader in China (Grint, 2011):

““Leadership is a matter of intelligence, trustworthiness, humaneness, courage, and discipline [...] Reliance on intelligence alone results in rebelliousness. Exercise of humaneness alone results in weakness. Fixation on trust results in folly. Dependence on the strength of courage results in violence. Excessive discipline and sternness in command result in cruelty. When one has all five virtues together, each appropriate to its function, then one can be a leader.””

A Brief History of Leadership

Prior to the 19th century, the concept of leadership had much less relevance than today: society relied on highly hierarchical and pre-appointed authoritarian figures, who came to occupy their position mostly based on family relations (Grint, 2011). After Sun Tzu's military masterpiece on leadership, we need to fast forward to the Renaissance (16th century) in order to identify an influential (and much criticized) philosophical work treating the theme of leadership: Machiavelli's "The Prince" (1513-1514). In this book, the Italian philosopher describes the state of politics of the time, and how leaders behave in order to maintain stability. "The fact is," he suggests in The Prince, "that a man who wants to act virtuously in every way necessarily comes to grief among so many who are not virtuous. Therefore, if a prince wants to maintain his rule he must learn how not to be virtuous, and to make use of this or not according to need" (Machiavelli, XV). Machiavelli argues that to protect the interest of a community, a prince must do whatever is necessary - for the greater good. As a consequence, the act must be contextualized and not judged based on some arbitrary moral rule. Thus, "It is far better to be feared than loved if you cannot be both." (Machiavelli, 1513-1514)

Leadership has then developed toward increasingly rational models, with the advent of Scientific Management during the first half of the 20th century (Taylorism and Fordism), and the progress in knowledge brought by technological advancements, which fostered a shift toward quantitative measures of rationality in management and leadership (e.g. Total Quality Management in the 1970s, Psychometrics in the 1990s).

Differences Between Managers and Leaders

Although perspectives on the differences between managers and leaders vary widely, an article by scholar Abraham Zaleznik (1977) represents a solid foundation to start from in the analysis of what makes leaders different from managers. Managing and leading are separate functions and require distinct skills. Consequently, there are some key differences between being a leader and being a manager. Managers are not necessarily good leaders. While the main role of managers is to maintain stability and order in an organization, leaders do more than that. In the essay, psychoanalyst and scholar Abraham Zaleznik explores in depth what he finds to be the main differences between managers and leaders, not only from a practical standpoint, but also as far as the psychological traits and attitudes that are characteristic of leaders and managers are concerned. Leaders and managers are viewed as archetypal representations of being. Zaleznik does not merely illustrate the difference between managers and leaders in an organizational setting. Instead, he describes psychological and attitudinal characteristics of human beings, which can be generalized outside of the organizational environment. For example, when the author suggests that managers are good at "maintaining stability" (Zaleznik, 1977), this can be linked to trait Conscientiousness, aspect Orderliness of the Big Five Personality framework (Poropat, 2009). As a consequence, we may infer that what characterizes a "manager" is a combination of particular psychological traits (e.g. High conscientiousness, low neuroticism, low openness to experience). which is also valid for leaders (e.g. High openness to experience, moderately high neuroticism).

Managers conserve and strive to maintain order in an organization, abiding by the rules. Leaders invent creatively. They have a higher purpose and value individuality and authentic relationships. In particular, Zaleznik reckons that leaders are mostly born so. There are, therefore, inherent psychological and physiological characteristics that are unique to leaders, especially when compared to managers. The analysis of leaders and managers made by Zaleznik is one which does not look at the concept of "leader" as the authoritative figure of a group. The leader is a personality and behavioral archetype. Zaleznik identifies five main dimensions based on which to compare managers and leaders: personality differences; attitude toward goals; conception of work; relationships and sense of self.

What Zaleznik pinpoints as key characteristics that make leaders differ from managers have to do with the approach to life and work leaders display. "Business leaders have much more in common with artists than they do with managers" (Zaleznik, 1977). According to Zaleznik, managers strive to maintain stability and order in the hierarchical and bureaucratic organizational structures, as opposed to leaders, who, instead, develop fresh solutions to problems. Leaders are in constant motion to innovate, develop new perspectives, break the mold. In addition, managers communicate through "signals" (vague, indirect, encoded, leaving a lot of space for personal interpretation), whereas leaders inspire through "messages" (powerful, emotionally charged, involving, inspiring, direct communication). Communication is, in fact, a powerful tool that leaders know how to use very well. Because of their intrinsic motivation, leaders like to inspire people to change, experiment, develop a vision, and do so by using messages that are rich in meaning and often foster emotional reactions.

““Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.””

Leadership theories

Understanding the root causes determining leadership characteristics is a convoluted endeavor. There are numerous theories attempting to depict what it is that makes a leader. Each one of them focuses on different aspects in order to try to explain what leaders have in common. The need for the different theories to coexist is necessary, in order to explain as accurately as possible how leaders are made (Zaccaro, 2007). There does not appear to be a single personality characteristic which can explain what makes a leader. Neither is there a specific attitudinal trait at the basis of leadership emergence. However, integrating leadership models from different psychological and practical aspects can be helpful in understanding better how leadership develops. Some of the most prominent leadership theories are:

Trait theory

The history of the world was the biography of great men

— (Carlyle, 1907, p. 18)

The "great men" hypothesis was one of the precursors of the trait theory of leadership.

"Leader traits can be defined as relatively coherent and integrated patterns of personal characteristics, reflecting a range of individual differences, that foster consistent leadership effectiveness across a variety of group and organizational situations" (Zaccaro, Kemp, Bader, 2004, p. 104). Personality traits are considered to be fixed, enduring over time, and hence foster a high degree of coherence across different situations. This is a significant limitation of the trait-based theory of leadership, which does not place enough relevance on the role of situations and attitudes of the individual. One of the bedrocks of personality trait theory is the "Big Five" Personality Traits model. This is a framework used to measure personality which is based on 5 dimensions (each one containing more specific aspects). They are: Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Neuroticism, Openness to Experience and Agreeableness. There is a substantial research base establishing the linkage between personality traits and leadership characteristics. One such piece of evidence is provided by a meta-analysis by Judge et al. (2002), who found significant correlations between personality traits and leadership, using the Big Five personality framework. As a matter of fact, certain traits were discovered to be highly predictive of leadership behavior and qualities. Particularly strong correlations were found between leadership and the following personality traits: high extraversion, high conscientiousness, low neuroticism (high emotional stability) and high openness to experience.

Behavioral Theory

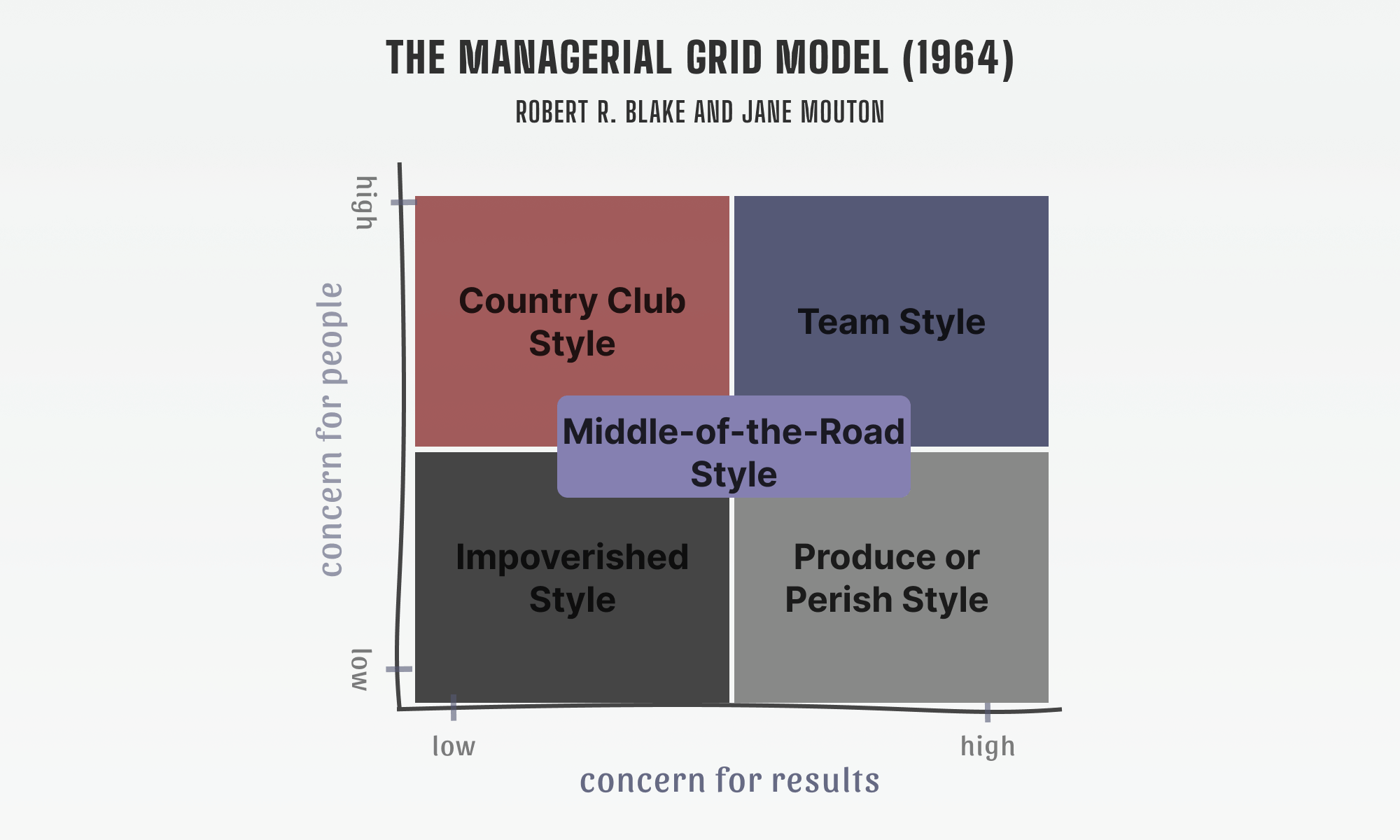

With the personality trait theory of leadership being too restrictive, a new school of thought trying to make sense of leadership developed from 1945, particularly thanks to the Ohio and Michigan leadership studies. It is the behavioral approach, depicted through the managerial grid model of leadership. This model focuses heavily on behaviors of leaders. Behaviors are malleable, variable, and in constant motion, based on the surrounding context and circumstances (Lewin et al., 1939). This view of leadership, therefore, looks at specific behaviors which are reflective of leadership effectiveness, where charisma is factored in (Conger & Kanungo, 1987). To do so, they are based on two identifiable dimensions: Initiating structure (task-oriented behaviors), and consideration (people-oriented behaviors).

As a consequence, the managerial grid of leadership behavior accounts for five possible behavioral approaches to leading:

Impoverished Management: low initiation and low consideration. The minimum necessary amount of work that has to be done to maintain organizational stability is exerted.

Authority-Compliance Management: high initiation and low consideration. The extreme focus on maximizing work efficiency interferes with the necessity to account for human needs.

Middle of the road management: medium initiation and medium consideration. In this behavioral approach to leadership, there is balance between making sure that work effectiveness is achieved, while ensuring high job satisfaction

Country club management: low initiation and high consideration. The thoughtful attention placed on human relationships and satisfaction hinders performance, resulting in an excessively friendly work environment.

Team management: high initiation and high consideration. There is high commitment, job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior, which leads to high performance and a relationship-based environment.

Situational Theory

Developed as a reaction to trait theory by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard (1969), the situational approach to leadership postulates that no single optimal psychographic profile of a leader exists. Different situations call for different characteristics and behaviors. There is no single superior leadership style.

Emotional Intelligence

Daniel Goleman, author of "Emotional Intelligence" (Bantam, 1995), postulates that there is a singular characteristic which truly makes the difference in leading effectively: emotional intelligence. With this concept, Goleman puts forward a strong argument explaining how leaders can behave most appropriately in order to achieve high performance and get results, which, the author asserts, is an agreed-upon answer to the question: what should leaders do? (Goleman, 2000)

IQ and technical skills are definitely important too, but they are merely "threshold capabilities", on top of which leaders must build and use emotional intelligence. The first pillar of emotional intelligence is that it can be developed over time, if worked on deliberately, open-mindedly, and with feedback from the people around us (Goleman, 2004). Emotional intelligence is a hybrid between a personality trait and an attitude to life and relationships. It is an individual characteristic which is composed of 5 aspects:

Self Awareness: "the ability to recognize and understand your moods, emotions, and drives, as well as their effect on others" (Goleman, 2004). People with self awareness are capable of speaking openly and accurately about their emotions, thoughts, and their impact on their work and life. They are eager for constructive criticism. By contrast, low self aware people often perceive criticism as a threat or failure. Self aware individuals know when to ask for help.

Self Regulation: the ability to control disruptive impulses, this component of emotional intelligence is associated with the propensity to "think before acting" (Goleman, 2004). A high level of self regulation is key to leadership because:

people who are in control of their emotions (reasonable people) create environments of trust and fairness. In turn, trust and fairness lead to high productivity and low infighting.

people who have high self regulation are much more capable to adapt to the rapidly changing market environment and technological advancements. "When a new program is announced, they don't panic; instead, they are able to seek out information", defer judgment, be aware, and manage change in the most appropriate way. (Goleman, 2004).

self regulation enhances integrity. This is a key quality not only in personal life, but also as an organizational value to have. In his essay on "What Makes a Leader", Goleman points out that many of the bad things that happen in companies are a result of impulsive and emotionally-charged behavior.

Motivation: a passion to work that goes beyond money or status. In the context of emotional intelligence, motivation is referred to as the intrinsic drive to achieve. High achievers are always seeking to learn, improve performance, raise the bar and challenge the status quo. They may have a tendency to wanting to stretch themselves too thin. However, if they use self awareness and self regulation, they strike a good balance of doing and performing to their best. High achievers also tend to be committed to the organization (Graham, 1991).

Empathy: the ability to understand the emotional makeup of other people, and tactfully treat them according to their emotional reactions. This does not mean trying to please everybody. Especially for a leader, "empathy means thoughtfully considering employees' feelings - along with other factors, in the process of making intelligent decisions" (Goleman, 2004). The increasing use of teams in organizational settings, globalization, and the growing need to retain talent are three essential factors that make empathy particularly valuable in today's world (Goleman, 2004). The skill of empathy, according to Goleman, can act as an antidote to cultural misunderstandings (globalization), and help create meaningful human connections (working in teams, retaining talent).

Social Skill: as Daniel Goleman puts it, "Social skill is friendliness with a purpose: moving people in the direction you desire." Socially skilled people work on the assumption that nothing important gets done alone. Unlike the other components of emotional intelligence, social skill seems to be widely considered a key leadership competency in organizations, as it is a common belief that being effective at managing relationships is very relevant in the domain of leadership.

Based on emotional intelligence and its components, research by consulting firm Hay/McBer identified, in the early 2000s, six leadership styles stemming from emotional intelligence characteristics. These leadership styles are not fixed and can be used together based on the situation and specific requirements of it. They are situational approaches. Daniel Goleman presents the six leadership styles in the 2000 HBR article "Leadership that Gets Results". In order to assess common patterns in leadership styles, the research team analyzed the climate in each executive's sphere of influence. The term climate refers to 6 key factors that influence an organization's working environment:

Flexibility: how free employees feel to innovate

the sense of responsibility employees perceive

The level of standards that people in the organization set

the sense of accuracy about performance feedback and rewards

the clarity people have about mission and values

the level of commitment to a common purpose

Six leadership styles were identified, two of which had a negative effect on organizational climate (Goleman, 2000). Below is a list of all the leadership styles identified, together with a representative phrase (as presented in the original article by Goleman) and related description.

Coercive style

"Do what I tell you."

The coercive style of leadership is, generally speaking, a detrimental situational approach to the overall climate of an organization. However, because it is a situational leadership style, it can be used sporadically and in very specific situations which require significant turnarounds or abrupt change.

Authoritative style

"Come with me."

Enthusiasm and clear vision are the hallmarks of authoritative leadership. The research presented in this paper indicates that this style of leadership is the most effective at raising the climate of an organization.

"The authoritative leader is a visionary; he motivates people by making clear to them how their work fits into a larger vision of the organization." (Goleman, 2000)

The authoritative leader provides honest feedback which always revolves around the grand vision of the organization. The standards of success and rewards are clear to everyone involved. An authoritative leader states the end goal but not the means to the end. The grand vision can be reached from different approaches. "Authoritative leaders give people the freedom to innovate, experiment, and take calculated risks" (Goleman, 2000). Although this style seems to be very effective in the majority of business situations, it may fail when employed with people who are more experienced than the leader, who may, in such cases, be perceived as deluded or excessively enthusiastic.

Affiliative style

"People come first."

This leadership style revolves around people and their sentiment. The affiliative leader manages by building relationships and reaping the benefits of such an approach, namely long-term loyalty. Flexibility is fostered by not imposing unnecessary structure where there is no need for it. Affiliative leaders provide ample positive feedback. They are also masters at building a sense of belonging among the people in the organization. They are natural relationship builders. This style can be particularly powerful when leaders are trying to build team harmony, increase morale, or repair broken trust. However, it should not be used alone, especially because of its bias toward positivity, which may make mediocrity well accepted. It can be very powerful when combined with the authoritative style.

Democratic style

"What do you think?"

The democratic approach to leadership works best when a leader is not sure about the direction to take and needs ideas and guidance from able employees. Because of its involving and conversation-oriented nature, this situational attitude is generally perceived positively by employees, who feel trusted upon. Nonetheless, its impact on climate is not as high as some of the other styles (i.e., Authoritative and Affiliative). Democratic leadership presents significant possible drawbacks, such as meetings where ideas are debated aimlessly and excessive insecurity, which can leave employees leaderless. Such an approach can lead to internal conflict, if not used carefully.

Pacesetting style

"Do as I do, now."

Setting extremely high-performance standards and leading by example, pacesetting leaders are obsessive in maximizing efficiency, demanding everyone around them to strive for the same. The way they communicate is encoded and signal-based (Zaleznik, 1977). Signals are encoded, indirect, impersonal, and leave a lot of space for interpretation, which often causes frustration and resentment among employees toward managers. Messages, on the other hand, are means of communication that may elicit strong emotional reactions, use imagery, and are direct. The communication style of pacesetting leaders makes use of signals, as opposed to messages. This leaves a lot of space for interpretation to employees, who can, as a result, feel overwhelmed and dissatisfied. According to Goleman, this leadership style can be successfully implemented in high-motivation work environments, where the majority of people are committed to high performance (e.g., in the legal world).

"Work becomes not a matter of doing one's best along a clear course so much as second-guessing what the leader wants." (Goleman, 2020)

Coaching style

"Try this."

Coaching leaders help employees find their strengths and weaknesses. They work on the development of the individual. The person's growth can then translate into better work performance and high morale. Of the six styles, this is the least often used, according to the research conducted and presented in the article. Some leaders say they do not have time to focus on single individuals, in such a fast-paced economy. Using a coaching attitude to leadership may work best when employees are intrinsically motivated to develop as individuals. As Abraham Zaleznik states in his 1977 article when detecting how leadership can be developed, "Great teachers take risks. They bet initially on the talent they perceive in younger people. And they risk emotional involvement in working closely with their juniors." Coaching and one-on-one relationships are of pivotal importance when it comes to making leaders, according to Zaleznik, who, although indirectly, considers the coaching style of leadership to be crucial in the development of leadership.

A Case Study of Leadership: Yvon Chouinard

"A value is a way of being or believing that we hold most important. Living into our values means that we do more than profess our values, we practice them. We walk our talk—we are clear about what we believe and hold important, and we take care that our intentions, words, thoughts, and behaviors align with those beliefs." (Brown, 2018, p. 186)

When the values of a leader align clearly with the company's activities and way of communicating, they are able to provide the kind of transparency that can set them apart. This is only one of the characteristics of Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, an American outdoor clothing company that strives to lead the way toward reversing the state of doing business. Harmonizing environmental and financial sustainability is at the center of the agenda of Patagonia, which has been in the industry for more than forty years. Chouinard had clear in mind the role of businesses in the environmental crisis going on ever since the time of birth of the company. He also was of the belief that organizations had the potential to reverse the status quo of doing things. And he enjoyed surfing, climbing, and Zen philosophy. He enjoyed surfing and climbing more than anything else, to the degree that Chouinard Equipment, the business selling pegs used in mountain climbing he started in the 50s "was just a way to pay the bills so we could go off on climbing trips" (Chouinard, 2010).

Patagonia was established in 1979 after Chouinard Equipment was sold. The mission statement of the company, in the beginning, went like this:

“Patagonia strives to build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, and use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.”

Applying Zen philosophy to doing business, Chouinard strove to maximize for doing things right and focus on the process rather than setting constant targets and falling prey to the hedonic treadmill. "In Zen Archery, you forget about the goal — hitting the bull's eye — and instead focus on all the individual movements involved in shooting an arrow. If you've perfected all the elements, you can't help but hit the center of the target" (Chouinard, 2010). The founder of Patagonia is a businessman on his own terms. He promotes an ambitious vision and values, which are clear-edged, hence attracting a very specific base of followership, which deeply shares the same vision of Chouinard. "We've rushed through a lot of CEOs and management teams that didn't understand what we are about...the values here are so deep...it is hard to find a CEO that will grow with the company" (Chouinard, 2002). The environmental component of Patagonia's mission spurred the company to remove anti-odor chemicals from its products in 1998, due to environmental and public health concerns, despite the growing nature of the market for anti-odor clothing at the time.

Management by absence is the theory practiced by Chouinard, who is the visionary of the company, delegating decision-making to the board of Patagonia. As Patagonia's founder himself puts it, "I am the entrepreneur who comes up with the wild and crazy idea and then dumps it on people to let them figure it out" ("The Way I Work", Inc.com). "When you have a lot of independent people working for you, you can't tell them what to do, or you will get a passive-aggressive response. Instead, you have to build a consensus", he continues.

When it comes to emotional intelligence and valuing human relationships, Chouinard asserts: "If I'm not in my blacksmith shop or in my office, I'm walking around. The worst managers try to manage behind a desk. The only way to manage is to walk around and talk to people. But I don't just walk around asking, "How are things going?" I have some specific things in mind that I want to talk to that person about. I meet most often with Casey Sheahan, our CEO, and Rose Marcario, our CFO and COO. I also get monthly reports from the heads of marketing, e-commerce, and other divisions. I always want to know what is not going well, so we can fix it." The seeming balance between delegation to "independent people", management by absence, and keeping constant human contacts to have a grasp of the situation of the business shows the peculiarity of Chouinard's leadership style, which is neither subject to micro-managing nor detachment from the "core" of the business activities.

"I love the idea of adapting myself to a situation rather than buying a lot of stuff. People don't need fancy stuff—they need gear that lasts and that works well. I've built my company based on that" (Chouinard,2013). While the approach to business of Patagonia may feel revolutionary and mold-breaking, especially during the early years, the company has been around for many decades and manages to strike a great balance between solid financial performance and social commitment to making the world a better place, one sustainable apparel at a time. As Chouinard affirms in his book Let My People Go Surfing, "It's okay to be eccentric, as long as you're rich; otherwise you're just crazy." This perfectly aligns with the vision of Patagonia, which wants to lead the corporate world toward a holistic approach to doing business, where the impact on the environment is fully accounted for. "If we wish to lead corporate America, we need to be profitable", the visionary founder mentions in his book. Or else, no one will believe that you can do business and be environmentally sustainable at the same time.

As Abraham Zaleznik argues in his 1977 essay, "business leaders have much more in common with artists than they do with managers." This is definitely the case of Yvon Chouinard, who is not merely setting a direction for his organization, but embodying that vision wholeheartedly, with emotional intelligence and business acumen.

If you find this content valuable, consider signing up for our weekly newsletter on life's essentials, Notion, the deep life here.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Part 1 → Effective Leadership

Antonakis, J. E., Cianciolo, A. T., & Sternberg, R. J. (2004). The nature of leadership. Sage Publications, Inc.

Arvey, R. D., Rotundo, M., Johnson, W., Zhang, Z., & McGue, M. (2006). The determinants of leadership role occupancy: Genetic and personality factors. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.10.009

Bennis, W. (2007). The challenges of leadership in the modern world: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 62(1), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.2

Bolden, R. (2004). What is leadership? Centre for Leadership Studies, University of Exeter.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to Lead (2018th ed.). Vermilion.

Bryman, A. (Ed.). (2011). The SAGE handbook of leadership. SAGE.

Commonwealth Club of California. (2016, November 17). Yvon Chouinard: Founding Patagonia & Living Simply (Full Program). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQlu95rzUTM

David Rooke and William R. Torbert. (n.d.). Seven Transformations of Leadership. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2005/04/seven-transformations-of-leadership

Day, D. V. (2012). Leadership.

DePree, M. (2011). Leadership is an art. Currency.

Dickerson, M. S., Benjamin Pring, David Kiron, and Desmond. (n.d.). Leadership’s Digital Transformation: Leading Purposefully in an Era of Context Collapse. MIT Sloan Management Review. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/leaderships-digital-transformation/

Dimovski, V., Marič, M., Miha, U., Đurica, N., & Ferjan, M. (2012). Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” and Implications for Leadership: Theoretical Discussion. Organizacija, 45, 151–158. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10051-012-0017-1

Dorfman, P. W., Howell, J. P., Hibino, S., Lee, J. K., Tate, U., & Bautista, A. (1997). Leadership in Western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. The Leadership Quarterly, 8(3), 233–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(97)90003-5

Drucker, P. F. (2004, June 1). What Makes an Effective Executive. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2004/06/what-makes-an-effective-executive

Gardner, J. (1993). On leadership. Simon and Schuster.

Goleman, D. (2000, March 1). Leadership That Gets Results. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2000/03/leadership-that-gets-results

Goleman, D. (2004, January 1). What Makes a Leader? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2004/01/what-makes-a-leader

Goleman, D. (2013, December 1). The Focused Leader. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/12/the-focused-leader

Goleman, D., & Boyatzis, R. E. (2008, September 1). Social Intelligence and the Biology of Leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2008/09/social-intelligence-and-the-biology-of-leadership

Graham, J. W. (1991). An essay on organizational citizenship behavior. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 4(4), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01385031

Grant, A. M. (2012). Leading with Meaning: Beneficiary Contact, Prosocial Impact, and the Performance Effects of Transformational Leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 458–476. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0588

Grint, K. (2011). A history of leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 3–14). Sage. http://webcat.warwick.ac.uk/record=b2346010

Hughes, R. L. (1993). Leadership: Enhancing the lessons of experience. ERIC.

Isaacson, W. (2011). Steve Jobs. Simon and Schuster.

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., & Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765

Kotter, J. P. (2001, December 1). What Leaders Really Do. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2001/12/what-leaders-really-do

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2006). The leadership challenge (Vol. 3). John Wiley & Sons.

Leadership. (2021). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Leadership&oldid=1014470886

Manfred, F. R. K. de V. (2013, December 18). The Eight Archetypes of Leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/12/the-eight-archetypes-of-leadership

Palmer, B., Walls, M., Burgess, Z., & Stough, C. (2001). Emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730110380174

Paumgarten, N. (2016, September 19). Patagonia’s Philosopher-King | The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/09/19/patagonias-philosopher-king

Poropat, A. (2009). A Meta-Analysis of the Five-Factor Model of Personality and Academic Performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

Prentice, W. C. H. (2004, January 1). Understanding Leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2004/01/understanding-leadership

Robbins, S., & Judge, T. A. (2019). Organizational Behavior. Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Rost, J. C. (1991). Leadership for the twenty-first century. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Schuetz, A. (2017). Effective Leadership and its Impact on an Organisation’s Success. Journal of Corporate Responsibility and Leadership, 3(3), 73. https://doi.org/10.12775/JCRL.2016.017

Shamir, B., House, R., & Arthur, M. (1993). The Motivational Effects of Charismatic Leadership: A Self-Concept Based Theory. Organization Science - ORGAN SCI, 4, 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.4.4.577

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. Penguin.

Sunnie Giles. (n.d.). The most important leadership competencies according to leaders around the world. https://hbr.org/2016/03/the-most-important-leadership-competencies-according-to-leaders-around-the-world

TED. (2010, May 4). How great leaders inspire action | Simon Sinek. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qp0HIF3SfI4

TEDx Talks. (2020, November 3). What working with psychopaths taught me about leadership | Nashater Deu Solheim | TEDxStavanger. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pKMgG9xIfEg

The Knowledge Project. (2020, December 22). Hire SLOW, Fire FAST | Kris Cordle | The Knowledge Project #99. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gXTuY7QoSOM

Warren, B., & Thomas, R. J. (2002, September 1). Crucibles of Leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2002/09/crucibles-of-leadership

Welch, L. (2013, March 12). The Way I Work: Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia. Inc.Com. https://www.inc.com/magazine/201303/liz-welch/the-way-i-work-yvon-chouinard-patagonia.html

Yvon Chouinard: Founding Patagonia & Living Simply (Full Program). YouTube. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQlu95rzUTM

Zaccaro, S., Dubrow, S., & Kolze, M. (2018). Leader Traits and Attributes (pp. 29–55). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506395029.n2

Zaccaro, S. J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.6

Zaleznik, A. (2004, January 1). Managers and Leaders: Are They Different? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2004/01/managers-and-leaders-are-they-different