Leadership in Organizational Change | Part 2 | Organizational Change

Organizational change management is a much relevant topic in the 21st century

What is organizational change?

While strong leadership requires specific personality and attitudinal characteristics, leaders also need to be able to navigate a constantly changing environment, by owning their responsibility and honing their adaptability skills (Kotter & Schlesinger, 2008). In the organizational environment, paradigms are constantly shifting, and particularly so in a period of time where technological progress has been at an all-time high (Zhexembayeva, 2020). Furthermore, the Covid-19 pandemic has wrought havoc in every industry and in the knowledge economy, increasing the need for leaders and managers to approach work from a different perspective, valuing human relationships above all (Schrage, Pring, Kiron & Dickerson, 2021). The journey to understanding the key leadership skills in the context of organizational change management begins with defining organizational change, a widely-researched area of organizational psychology, which is incredibly relevant in the 21st century.

According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, organizational change is "a process in which a large company or organization changes its working methods or aims, for example in order to develop and deal with new situations or markets". Change can be manifested in numerous forms and degrees of intensity throughout the lifetime of organizations, from shallow to transformational (Robbins & Judge, 2019). Transformational change is characterized by a complete makeover of "the way we do things around here" in an organization. This type of change is often what makes the most number of obstacles arise, because of its stability-breaking purpose. As a consequence, "Change management is the process of continually renewing an organization's direction, structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers" (Moran & Brightman, 2000). In such an "ever-changing" environment, organizational change is often depicted as a linear, rational process by most of the classical scientific literature on the topic. However, reality is much more nuanced than that, and, as Graetz and Smith (2010) argue, the need for a multi-philosophy approach to change management is what organizations truly need, where continuity and change are harmoniously balanced in the process (Graetz & Smith, 2010). Such a cross-philosophy attitude toward change is rooted in the belief that change is non-linear, embedded in complex organizational mechanisms that require flexible, case-specific assumptions and beliefs about the change process. According to Graetz and Smith, there are ten philosophies of change that can be identified:

The biological philosophy refers to a way of viewing change as a metaphorical representation of "individual experiences of members of a species" (Graetz & Smith, 2010). This theory takes a developmental approach to the analysis of organizations, looking at them as entities with a life cycle spanning from start up to divestment.

The rational philosophy is concerned with a linear and strategic approach to change management, where external events of the organization are considered exogenous variables that often cannot be controlled by change agents. According to this doctrine, change can be initiated at any time, and is the complete responsibility of managers and leaders.

The institutional philosophy of change has its foundation in the belief that companies are often forced to change due to the surrounding institutional environment they are embedded in (e.g., the industry), whose elements are in constant evolution. Change, therefore, is mostly reactive and dependent on how well-rooted in institutions firms are (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991).

The resource philosophy. According to proponents of this theory, the success of an organizational change program stems from the ability of a company to manage and deploy resources, which are scarce by definition. As a consequence, change has to do with internal mechanisms intrinsic to the organization, and the external environment has very little influence on the change program.

The contingency philosophy is based on the assumption that intertwined organizational and environmental variables are in constant motion. Change programs in this context are aimed at managing the shifting elements by re-establishing order from chaos. This philosophy of change is highly situational and circumstance-specific.

The psychological philosophy of change looks at individuals, with their emotions and resistance to change, as the foremost important element of change. By considering people at the center of change programs, proponents of this philosophy aim to manage change by focusing on individuals and their psychological responses to change. This is in contrast to the rational and mechanistic philosophy of change, which are, instead, process-centered.

The political philosophy has its foundation on the assumption that organizations are made of numerous, often conflicting, coalitions of individuals each with their own interests and agendas. Owing to the fact that each coalition attempts to change the status quo and meet their own interests, change in this context is usually perceived as high-conflict and driven by strong beliefs.

The cultural philosophy. Proponents of this theory postulate that the element at the center of organizational change are groups (the collective), as opposed to individuals (as argued by the psychological philosophy). As a consequence, change is driven by shared values and cultural forces often at play subconsciously within people.

The systems philosophy is based on the belief that organizations are complex systems, where the key component can be found in the interrelation among departments and functions. In this view, change takes place holistically in the company, with every unit involved, whether directly or indirectly, in the change program.

The postmodern philosophy. Subscribers of this theory posit that there is no such thing as universal reality. Change is a socially-constructed mechanism characterized by a high degree of fragmentation, chaos and uncertainty.

In such a fast-paced world, Graetz and Smith (2010) argue, what can make organizations stand out is the ability to merge more than one change philosophy together in the change management process. It is only in this way that change can be effective and not based on bounded philosophies, each of which misses some fundamental parts of the human mind or the change mechanisms. In order to understand this view of change more accurately, we first need to step back, review the most established concepts around organizational change, and figure out the psychological reasons for which we need to form mental models around the science and practice of effective change management.

“There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.” (Machiavelli, The Prince)

The Role of Psychology in Organizational Change

Resistance to Change

One of the constants in the field of organizational change management appears to be resistance to change. Resistance to change seems to be an inherent natural tendency of human beings, and it is often associated, in the context of change, with stubborn employees holding onto the status quo (Ford D., Ford W., & D'Amelio, 2008). There is more to this story, however. First of all, let's define the term resistance. In physics, resistance is a measure of the opposition to current flow in an electrical circuit. According to the Cambridge dictionary, resistance is "a force that acts to stop the progress of something or make it slower." In the case of organizational change, resistance manifests itself through vivid or latent opposition from some individuals or coalitions of people to the change program. In order to understand the reasons behind such a prominent presence of resistance in organizational change, we need to turn to evolutionary psychology. Besides its technical (or practical) aspect, change also has a social element to it. "The social aspect of the change refers to the way those affected by it think it will alter their established relationships in the organization" (Lawrence, 1969). This nature of resistance to change is particularly prominent, according to Lawrence, when change is imposed from the top down by change initiators. To explain further, incremental changes can be witnessed very often in the workplace, and they encounter no resistance when they are ideated and implemented at a team level, where there are established relationships of trust among components of a group. On the other hand, stubborn resistance may take place when management introduces change, mostly focusing on the practical aspect of it. By overlooking the crucial human yearning for belonging and stability, change agents often provoke a freeze, flight, fight response (Cannon, 1927) to stressors stemming from the perceived threat of change. This limbic response potentially hinders the ability for change programs to succeed in the long run.

The internal state of resistance to shifting habits inherent to human beings is not merely displayed by employees attempting to maintain a sense of control over their work and social routines. As a matter of fact, resistance can also happen at the management level, often residing in change initiators themselves (Ford et al., 2008). This is a point of view of resistance to change which is normally overlooked, especially when wanting to analyze the possible strategies for overcoming resistance to change among employees (e.g., clear communication, participation, building relationships). As French philosopher Voltaire stated in his novel Candide: Optimism, "one must cultivate one's own garden" (Voltaire, 1759). In the context of organizational change, initiators need to be aware of their own inner contrasting sensations and set intentions straight upfront, before intervening to reverse resistance to change at a group level. In particular, it appears that change agents often fall prey to sensemaking (Ford et. al, 2008): by perceiving resistance as something which is "over there", external to oneself, they attempt to rationalize the fact by seeing themselves as "victims" of resistance to change. Sensemaking is just another by-product of cognitive biases and heuristics (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) human beings are powerfully subject to, to varying degrees. Understanding some of the most common mental flaws at play in the domain of organizational change management and how to overcome them may be pivotal to managing change optimally (both within oneself and externally).

Human Biases in Resistance to Change

Although the argument for developing an awareness of the prominence of biases in the human mind may appear to be a manifesto for using rationality as much as possible, this is not exactly the case. As a matter of fact, we need not neglect the role of intuition in the context of decision making, for example. The key concept here is, however, to delay intuition, as Kahneman (2021) points out. The goal of being aware of our own mental fallacies is "to not decide prematurely, and to not have intuitions very early" (Kahneman, 2021). "You cannot make decisions without them being endorsed by your intuition. You have to feel conviction" (Kahneman, 2021). Being aware of errors of judgment (cognitive biases) allows us to not fall prey to jumping to conclusions too early, which is often followed by coming up with seemingly reasonable arguments supporting our choice (rationalization). When it comes to overcoming resistance to change, this entails letting go of the initial impulsive reaction stemming from fear of change, by objectively analyzing the circumstances before leaning into an attitude toward the change program.

Status quo bias (conformity) & Loss Aversion

The inherent loss-averse nature of human beings makes it difficult to venture into the unknown, as is the case in organizational change management programs. The status quo bias is the tendency we have to be reluctant to change when the current state of affairs is satisfactory enough. As a matter of fact, in such a context, possible losses "loom larger than the advantages" of leaving the status quo (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1991). The status quo bias has its foundations, therefore, in loss aversion (Kahneman et al., 1991), the proclivity to perceive hypothetical losses to be much more prominent than the improvements that change can bring. As a consequence of our resistance to venturing into novel territory, we tend to hold on to the status quo, reluctant to change. Although cognitive biases are inevitably present in our minds, being aware of their power on the way we make decisions can make the difference in not falling prey to them. In addition to this, the degree to which individuals are subject to the status quo bias is also dependent on personality traits: those who score low in openness to experience are more likely to stick to the status quo and display an inherent resistance to change (Natàlio, 2019). As Kahneman et. al point out (1991), the status quo bias and the intensity of loss aversion depend on the framing of the gains and losses in a decision/choice. In the change management context, as Ryan (2016) postulates, framing failure-to-transform in terms of losses is a great choice, due to the higher weight individuals place on losses as compared to gains:

“If we don’t embark upon this transformation program, we will fail to maintain pace with competitors and…” (Ryan, 2016)

The relevance of framing in the emergence of the status quo bias, however, has seen some contrasting evidence in the literature, the main source of which is a paper by Samuelson and Zeckhauser (1988), where the authors argue that the results of their experiment on the status quo bias did not show any correlation between framing and cognitive biases, hence positing that the "status quo bias is a general experimental finding - consistent with, but not solely prompted by, loss aversion" (Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988).

Overconfidence

"An unbiased appreciation of uncertainty is a cornerstone of rationality—but that is not what people and organizations want. Extreme uncertainty is paralyzing under dangerous circumstances, and the admission that one is merely guessing is especially unacceptable when the stakes are high. Acting on pretended knowledge is often the preferred solution." (Kahneman, 2013)

As Kahneman points out (2013), "what you see is all there is". We are stuck to our own, seemingly rational stories of the world around us and its functioning. This is the illusion of validity (Kahneman, 2011): confidence, broadly speaking, is a feeling, rather than a rational evaluation of probability. It is grounded on the stories we tell ourselves and their seemingly rational nature. In fact, "overconfidence arises because people are often blind to their own blindness" (Kahneman, 2011). The overconfidence bias is "an expectancy of a personal success probability inappropriately higher than the objective probability would warrant" (Langer, 1975). Attempting to eradicate the overconfidence bias is a task that requires we ask two questions, according to Kahneman (2011):

"Is the environment in which the judgment is made sufficiently regular to enable predictions from the available evidence?"

"Do the professionals have an adequate opportunity to learn the cues and the regularities?"

"After a few years of hard work, managers may be tempted to declare victory with the first clear performance improvement. While celebrating a win is fine, declaring the war won can be catastrophic." (Kotter, 1995)

Ultimately, creating environments in which uncertainty is allowed may be of crucial importance, particularly in an organizational change program. The system need not reward the most overconfident individual, but the most competent and rational one. It is only in this way that change programs may increase their chance of success in the long term.

Self-fulfilling prophecy and Pygmalion effect

Change initiators are just as likely to fall prey to cognitive biases as change recipients (Ford et al., 2008). The most prominent biases often residing in change agents are the self-fulfilling prophecy (Merton, 1948) and the Pygmalion effect (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). "If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences" (Merton, 1948). This statement summarizes the self-fulfilling prophecy bias, which can be defined more precisely as "a person's belief, false at the time, that a certain event will happen in the future. The person holding the belief then behaves as if the event is an inevitable occurrence, making sense of the actions and communications of others in such a way as to confirm the prophecy. In so doing, he or she enacts a world that appears as an insightful awareness of reality, rather than a product of his or her own authorship"(Forder at al., 2008). The Pygmalion effect presents the same characteristics of the self-fulfilling prophecy bias, with the key difference being that the former is "one person's expectations of another's behavior" (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968), whereas the latter is an expectation about external circumstances.

In the domain of organizational change management, these biases apply to change initiators in two ways:

Since resistance to change is often considered a non-negotiable variable in change programs, change agents expecting resistance are very likely to find it (self-fulfilling prophecy), possibly fueled by their defensive or top-down behavior patterns displayed throughout the change management;

The Pygmalion effect can be used to change agents' advantage, and as a deterrent of the self-fulfilling prophecy bias, owing to the opposing nature of this nudge, the awareness of which may foster a climate of positive reinforcement and trust among the people involved in the change program. By "expecting" change recipients to be collaborative and communicating this thoroughly during the change process, initiators may unlock the potential of human cooperation during the change effort, which is a fundamental element of a successful program.

Self-serving bias

The self-serving bias is the tendency for individuals to attribute success to their own ability and effort, but blame failure to external circumstances (Miller & Ross, 1975). This bias can often be witnessed among change initiators themselves, who may respond impulsively to the urgency and stress caused by transformational change management processes (Kotter, 1975) by self-enhancing and self-protecting their persona and self-worth, in order to attempt to make sense of the world around them (Shepperd, Malone, Sweeny, 2008). Self-enhancement is a psychological motivational mechanism that aims at increasing our self-worth and value in society (Snyder, Stephan, & Rosenfield, 1976). This is closely linked to self-presentation, the importance we tend to place on how other people perceive us (Schlenker, 1980), which drives our aim to convey specific characteristics of ourselves. The influence of the self-serving bias may vary based on individual characteristics and personality traits. In the context of organizational change management, the awareness of this cognitive and motivational fallacy can empower change leaders to maintain a balanced approach to wins and losses along the journey of change, by understanding that their self-worth is not significantly bolstered by success and undermined by failure in the short term. Instead, the process of change takes time, effort, and detachment of the ego, in order for the mission to remain clear and focused.

Competing commitments and cognitive dissonance

"A competing commitment is a subconscious, hidden goal that conflicts with our stated commitments." (Kegan & Lahey, 2001)

In their 2001 article, Kegan & Lahey attempt to depict "the real reason people won't change" by presenting the concept of competing commitments. When it comes to changing the status quo, there are vivid and latent objectives that are present within the organization and individuals. While the stated goals of change may be seemingly shared by everyone in a restructuring program, each individual may also have his/her own competing commitments, which are often subconscious. These internal friction mechanisms need to be uncovered in order for immunity to change to be eradicated (Kegan & Lahey, 2001). In order to get rid of competing commitments, change actors need to first understand that these are a form of self-protection against big assumptions: "deeply rooted beliefs about themselves and the world around them" (Kegan & Lahey, 2001). Big assumptions must be challenged so as to break free from competing commitments by (1) looking for contrary evidence, (2) analyzing the history of their development during our lifetime, (3) and testing the assumption in order to evaluate how it holds in the real world (Kegan & Lahey, 2001). Below is an example of competing commitments in the context of change (Kegan & Lahey, 2001): Marc is a leader at the organization he works for. He believes in the importance of having a higher purpose that guides every business; a north star that takes into account the impact of the organization's activities on society at large. Yet, if you asked Marc's co-workers, they would tell you that his pragmatism and strategic day-to-day decisions do not match this belief of Marc, who always maximizes for financial results as opposed to social value creation. This perceived cognitive dissonance keeps Marc's co-workers at a distance. Despite the many reminders regarding the importance of a higher purpose that drives every business decision, as well as the stated willingness to change by Marc, the experienced leader seems to always get back to his old patterns. Deeply inside, Marc holds a competing commitment: being able to provide for his family and children, in the long run, is a key value for him, who grew up in a high-masculinity (Hofstede, 1980) environment, in which being the financial pillar of the family is a crucial part of the male identity. As a consequence, Marc keeps following his real, deep, maybe subconscious principle, which is at the core of every decision he makes.

Theoretical Models of Change Management

Insofar as the psychological aspect of organizational change management is relevant in the effectiveness of a change program, it is only one side of the coin. Together with understanding the human psyche, as a matter of fact, there is the need to take action and apply change at a practical (or "hard") level. The pace of change and strategy to put into action depend on four factors (Kotter & Schlesinger, 2008): how much resistance is anticipated; the power of change initiators vis-a-vis change recipients (the lower the power of the initiator, the slower the process of change); how relevant data for the change are distributed and how much collaboration is needed; the stakes involved (e.g., the context in which change takes place, consequences of resistance). Regardless of the speed of the change process, three of the most comprehensive change management frameworks that are often used in transformation programs include: Kotter's 8-step process, Lewins's 3-step framework, Theory E & Theory O (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, 2015).

Kotter's 8-step process

In his landmark article "Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail" (1995), John P. Kotter introduces an eight-step model to change management, which is now renowned and named after its inventor. Kotter's eight-step process of implementing effective change is rooted in the assumption that transformation is a process rather than a once-in-a-while event (Kotter, 1995). As such, it must be dealt with through chronological stages that build on each other. Skipping any of the steps listed in this framework only provides the illusion of progress in the short term (Kotter, 1995).

Establish a sense of urgency: transformational change begins with the identification of some potential expansion (e.g., an emerging market that everyone seems to ignore) or risks in the company's surrounding, whether originating internally or externally. These opportunities or threats need then to be communicated broadly and emphatically in the corporation, especially when there is a crisis prospect identified. This first step is essential, because starting directly with change and skipping the initial phase of honest and urgent communication might result in quick failure (Kotter, 1995).

"When is the urgency rate high enough? From what I have seen, the answer is when about 75% of a company’s management is honestly convinced that business as usual is totally unacceptable." (Kotter, 1995)

Form a powerful guiding coalition: in order for the process of change to begin effectively, there needs to be a committed group of people leading it. The guiding coalition can be composed of few people in the early stage, but it needs to grow as the change program moves along the ensuing milestones. In this phase of coalition establishment, organizational roles and hierarchies tend to become flatter and more blurred, with non-senior employees taking charge of the change, although committed senior managers must always be the guides of the coalition, as experience and careful actions are necessary in every decision (Kotter, 1995).

"Efforts that don’t have a powerful enough guiding coalition can make apparent progress for a while. But, sooner or later, the opposition gathers itself together and stops the change." (Kotter, 1995)

Create a vision: the vision of the organization is "a picture of the future that is relatively easy to communicate and appeals to customers, stockholders, and employees" (Kotter, 1995). In this stage of the change process, the guiding coalition needs to work on developing an easy-to-convey and emotionally significant vision for the change program, as well as the strategy to communicate the vision successfully.

"If you can’t communicate the vision to someone in five minutes or less and get a reaction that signifies both understanding and interest, you are not done." (Kotter, 1995)

Communicate the vision: companies must use every possible medium of communication to spread the vision and details about the organizational change. The communication process of the vision, however, is not merely theoretical. In fact, it has to manifest also in the behaviors of members of the guiding coalition, who must "walk the talk" and embody the new corporate culture. Word-based communication channels include meetings, newsletters, or lively articles about what is planned to happen (Kotter, 1995).

"Communication comes in both words and deeds, and the latter are often the most powerful form. Nothing undermines change more than behavior by important individuals that is inconsistent with their words." (Kotter, 1995)

Empower others to act on the vision: at this stage of the change process, it is pivotal to facilitate the implementation of the vision organization-wide. In order to foster this, the guiding coalition needs to remove any barriers and obstacles undermining the development of new ideas, risk taking, or newly-implemented processes. "The more people involved, the better" (Kotter, 1995). Sometimes, the biggest obstacle to the implementation of the new vision is the organizational structure itself, which might be rigid and heavily hierarchical.

"In the first half of a transformation, no organization has the momentum, power, or time to get rid of all obstacles. But the big ones must be confronted and removed." (Kotter, 1995)

Plan for and create short-term wins: short-term wins that are clearly identifiable are essential in the change process to build confidence and positive reward systems among employees. If the change is taking place effectively, small wins are visible and undisputable. They can manifest in increased market share, higher customer satisfaction, or increase in revenues. Acknowledging small wins is pivotal in order to prevent resistance from compounding, which can happen if employees are not provided with tangible progress.

"When it becomes clear to people that major change will take a long time, urgency levels can drop. Commitments to produce short-term wins help keep the urgency level up and force detailed analytical thinking that can clarify or revise visions." (Kotter, 1995)

Consolidate improvements and produce still more change: with the status quo bias always present in the background of individuals' brains, decreasing the level of effort and attention too early can be catastrophic. So too can be giving excessive weight to short-term wins, which must not be confused for "winning the war" (Kotter, 1995). Transformational change takes years, not months.

"Instead of declaring victory, leaders of successful efforts use the credibility afforded by short-term wins to tackle even bigger problems." (Kotter, 1995)

Institutionalize new approaches: change efforts truly become reality when new processes become "the way we do things around here", embedded in the culture of the organization. Kotter (1995) presents two factors that are pivotal to institutionalizing change in the culture of the business:

showing people how the new approaches and behaviors have improved performance by communicating clearly, as you don't want people to be left by themselves making connections without the broad picture of how the change program played out.

taking sufficient time to make sure that the next generation of top management truly personifies the new culture arising from the change process.

Kotter's eight-step model of change is one of the most widely used and a reference point in the organizational change management literature. However, it presents some potential fallacies in its applicability in the real world. Some of these include (Appelbaum, Habashy, Malo, Shafiq, 2012): the rigidity of the model, which must be followed in chronological order, makes it possibly detached from reality, when the change process is entangled and complex, with many inputs coming from different departments and loci; the model is not detailed enough to manage all the difficulties arising along the path toward change (Appelbaum et. al, 2012).

Lewin's 3-step framework

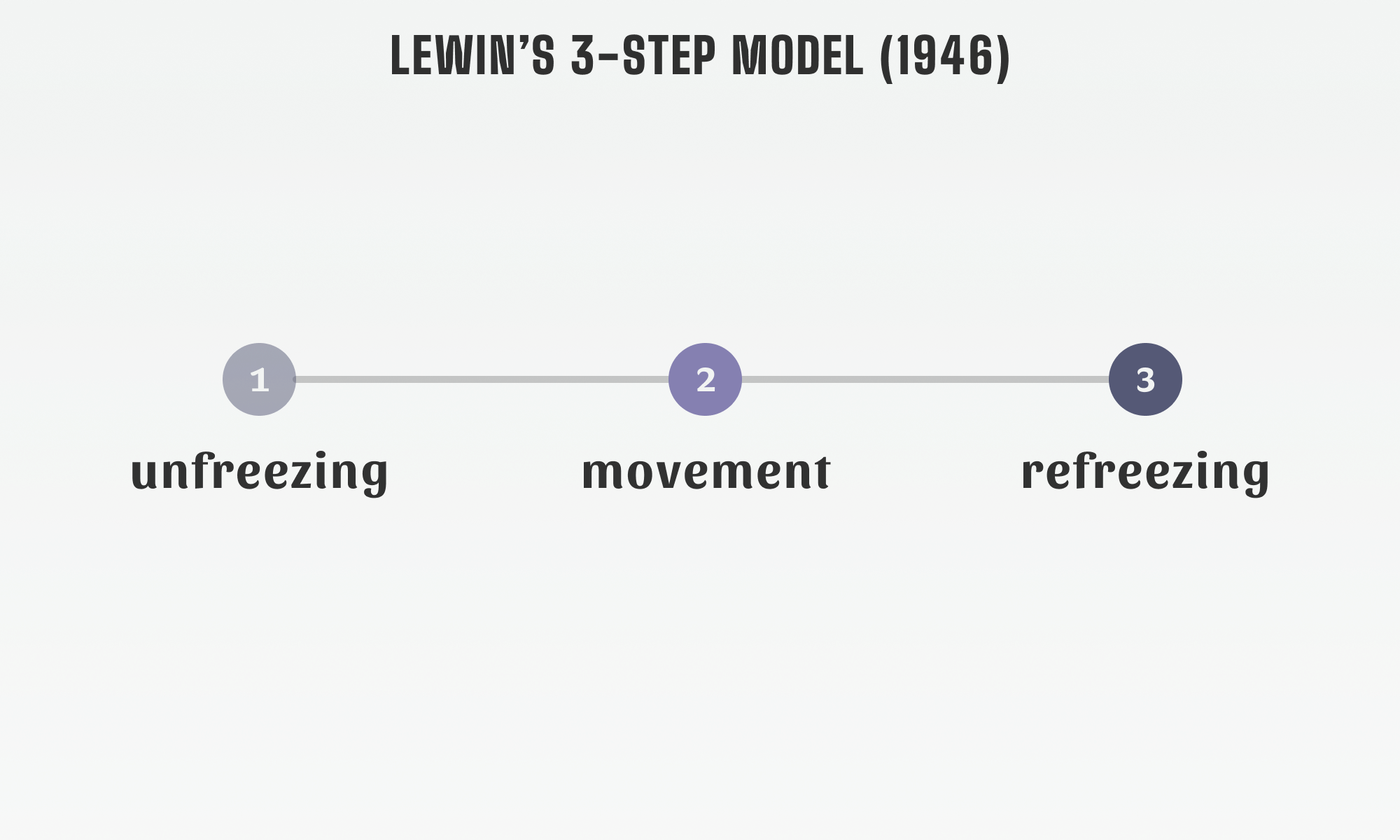

Unfreezing, movement, and refreezing are the three crucial steps to change management according to Lewin’s three-step model.

"A change toward a higher level of group performance is frequently short-lived; after a "shot in the arm", group life soon returns to the previous level" (Lewin, 1947)

Kurt Lewin, after whom the "3-Step Model" of change management was named, has been a pioneer in the development of organizational psychology as we know it today. He is regarded as the founder of organizational development and applied behavioral science (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, 2015). In 1946, the German-American psychologist devised the 3-Step model of change, although some evidence suggests that the model only came into existence after Lewin's death (Cummings, Bridgman, Brown, 2016). The 3-step framework of organizational change is composed of macro stages that can be recognized in every change process:

Unfreezing: at the inception of change, the status quo needs to be questioned and "unfrozen" in order to set up the most optimal environment for change to take place. The unfreezing stage of change management involves the increase of driving forces thanks to which behavior is moved away from the status quo, while decreasing restraining forces (i.e., those that pull behavior back to the status quo). This facilitates the transition to a new way of "doing things". Driving forces must be greater than restraining forces in order for change to occur successfully. As a matter of fact, there must be significant reasons that convince change receivers of the benefits the new state of things will bring to the organization (Bozak, 2003). Driving and restraining forces can be internal or external to the change-making organization. Internal driving forces may include lack of innovation, the need for higher performance or higher profits, the need to change leadership or culture. External driving forces encompass but are not limited to: high pressure from competition, change in consumer behavior, and new industry trends.

Movement: the second (and longest) stage of the change process consists of actually implementing change and instituting new rules and behaviors organization-wide (Lewin, 1947). This is often the most difficult part of organizational change management, and where the most resistance may be encountered both at a group level and within rigid organizational structures themselves (Lewin, 1947). "To break open the shell of complacency and self-righteousness it is sometimes necessary to bring about deliberately an emotional stir up" (Lewin, 1947).

Refreezing: remaining at the newly established level of "business as usual" is as much of an effort as the previous steps of change management. In fact, according to Lewin (1947), "permanency" of the new state of things must be included in the objective of change that is laid out during the unfreezing stage. If new behaviors and procedures are not reinforced and positively rewarded, the threat of going back to the status quo can become reality fairly quickly. As Kotter (1995) also emphasizes, short-term wins do not correspond to success in the long-term game of change management. Letting one's guard down when it is too early may be just as detrimental as failing at change implementation.

Theory E and Theory O

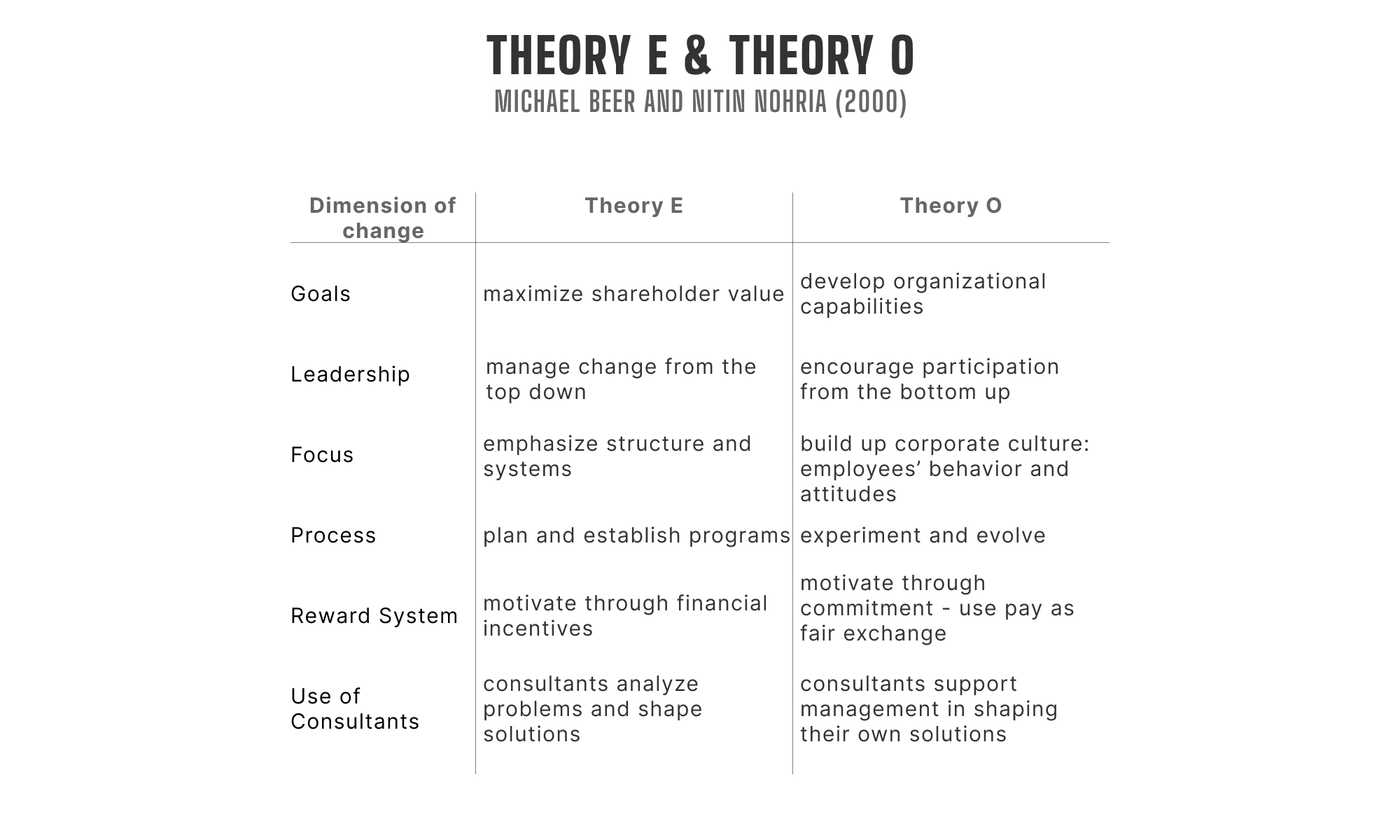

The differences between Theory E and Theory O with regards to some key aspects of change management

An additional theory of change management is one developed by Beer and Nohria (2000): "Theory E and Theory O". The aim of this view of change management is to balance the "hard" side of change management with "soft" skills. Theory E is the management of stakeholders' value throughout the change management process (Freeman, 1984): "this hard approach boosts returns through economic incentives, drastic layoffs, and restructuring" (Beer & Nohria, 2000). Theory O of change focuses on building corporate culture and fostering trust and emotional commitment in the organization. Since these two theories of change are opposites, leaning excessively into only one of the two may increase the chances of failure (Beer & Nohria, 2000). As a matter of fact, overleveraging Theory E produces top-down approaches to restructuring, which is often the catalyst for heavy resistance (Lawrence, 1969), whereas only making use of Theory O may lead to weak strategies, which do not account at all for the practical aspect of change. According to Beer and Nohria (2000), the implementation of Theory E and O must follow a chronological order, as the application of change is easier if started from Theory E. This is due to the "sense of betrayal" that would stem from the adoption of Theory O before Theory E (Beer & Nohria, 2000).

Leadership and Organizational Change Management

Transformational leadership involves “motivating followers to transcend their own self-interests for the sake of the team, the organization or the larger polity” (Shamir, House, Arthur, 1993). The entire process of organizational change management, when radical, is a source of stress, possible conflict, and psychological resistance. Fostering an environment where work is perceived by the majority of people as meaningful is of key relevance for the potential success of the change program. Meaningful work arises “when an individual perceives an authentic connection between work and a broader transcendent life purpose beyond the self” (Bailey and Madden, 2016). Effective transformational leadership calls for the design, embodiment, and compelling communication of an aspirational vision that is oriented toward adding value to society at large (Shamir et al., 1993). The challenge resides in ensuring that meaningfulness does not get undermined by transmitting a sense of "artificiality and manipulation" (Bailey and Madden, 2016). While the process of change management may result in conflicting emotions and inner resistance, there is a reflective component to meaningful work (Bailey and Madden, 2016): meaningfulness is not always a positive experience in the moment it is experienced. Meaning can be found in non-routine moments, where the unexpected can happen at any time, and difficulty arises. This is what Bennis and Thomas (2002) name "crucibles of leadership", and what Viktor Frankl examines in his book "Man's Search for Meaning" (1946). Due to the retrospective nature of meaningfulness, change leaders need to reinforce behaviors that increase the power of driving forces toward the new state of things (Lewin, 1947), while believing in the importance of helping change receivers "connect the dots" of the progress made on the implementation of change (Kotter, 1995), rather than leaving them alone in figuring this out. As a result, effective leadership during change management begins from an honest and clear purpose from which the entire plan stems. The purpose is communicated transparently throughout the change program, while a systematic and iterative strategic plan is laid out beforehand. Leaders are required to "ramble with vulnerability", lean into courage (Brown, 2018), and lead change management by embodying the direction toward which the organization is headed, every day.

Leadership in Transformational Organizational Change: Airbnb and Covid-19

When the worldwide pandemic Covid-19 wrought havoc on the entire world at the beginning of 2020, travel-and-experiences company Airbnb was not left intact from the wave of restrictions put in place by governments all around the globe. As an organization operating in the tourism industry, Airbnb witnessed an all-time-high cancellation rate compounded with no reservations, all at once. The firm lost around 80% of revenues in 8 weeks (Chesky, 2021). The inevitable decline of business as usual caused by external uncontrollable events called CEO Brian Chesky and the whole company for brave leadership, intelligent management, and authentic communication. As Squire Bill Widener once put it (quote attributed by Theodore Roosevelt in his autobiography): “Do what you can, with what you’ve got, where you are” (Roosevelt, 2006). The organization needed to pivot and adapt to the current environment very quickly, in order to not get out of business in no time. Resilience was needed. And resilience might be the main concept that seems to have characterized the response of Brian Chesky and Airbnb. According to the Cambridge English dictionary, resilience is "the ability of a substance to return to its usual shape after being bent, stretched, or pressed".

On account of the huge downturn in the economic and business situation of Airbnb, the company had to undergo drastic job cuts during the first months of 2020. One of the possibly toughest tasks of laying off employees in such an uncertain context for everyone is communication. It is how to communicate the decisions made by the management in an effective manner, providing sufficient support and transparently stating the reasons behind such a change occurring. In his letter to employees (May 2020), CEO Brian Chesky leans into emotional intelligence and honest communication while explaining the job cuts that are going to inevitably take place at the company. First of all, Chesky begins by clearly addressing the "elephant in the room" in the first paragraph: "Today, I must confirm that we are reducing the size of the Airbnb workforce" (Chesky, 2020). However, he does not stop at that. He continues the message explaining systematically the details that made the management arrive at the decision, the guiding principles behind the decision, and "what we are doing for those leaving, and what will happen next". Among the services provided for those leaving Airbnb, there are health insurance throughout 2020, mental health support, career services to increase the chances of finding a new position, and the permission to keep the company-provided laptop, as "a computer is an important tool to find new work" (Chesky, 2020). Chesky embodies Airbnb's vision of belonging in the letter to employees, by making it clear that no one will be left alone, with personal and organization-wide responsibility shining through every sentence.

"Culture is what you do in the darkest of days" (Chesky, 2021)

In a period of time that CEO Brian Chesky defines as the most stressful of his life, packed with sleepless nights (Chesky, 2021), but also as the most defining moment for the development of his leadership, Airbnb unleashed the potential of boundaries in creativity. The organization managed to dynamically pivot to expanding their business activities and developing "virtual experiences" that could replace the core business of the company, irreversibly impacted by the pandemic, at least in the short term. Remaining true to the company's values and principles, Airbnb has been navigating the crises courageously, and went public in December 2020, convincing investors and regulators of the solidity of the organization and his clear future direction in such a human-needs-based industry as travel and experiences. The Initial Public Offering (IPO) of Airbnb was the biggest of 2020, at more than 100 billion US$ (Hussain and Franklin, 2020), putting an end to a tumultuous year that CEO Chesky describes as a "rebirth" of the company (Chesky, 2021), and an authentic opportunity to hone leadership and change management skills in a time of deep crisis.

Conclusion

As Machiavelli points out in The Prince, "instituting a new order of things" is one of the most challenging endeavors one can face in life. This seems to be exactly the case in the context of organizational change management. Organizations are fundamentally composed of individuals, who are nested in groups, who form the wider organizational structure. Due to the cognitive biases of individuals, resistance to change is considered an inescapable part of any change program by scientific literature. Framing resistance to change with an internal locus of control is pivotal for change makers to not fall prey to their mental fallacies (e.g., self-fulfilling prophecy), which may significantly hinder progress. Besides being aware of the fundamental psychological aspects of change management, change agents need to use a careful, systematic approach to organizational change. This implies utilizing one of the frameworks described above (e.g., Kotter's 8-step process) without overlooking the relevance of "making change stick" by not lowering the guard before the new state of things is embedded in the organizational culture.

Above all, change management requires leaders who can fully embody the change vision and the company culture, without over-imposing their ideas, but rather using an authentic, emotionally intelligent approach to change. Leaders must begin the change journey from themselves, truly understanding the new dynamics and "cultivating their own garden" before venturing into the unknown territory of acting as change agents. Transformational change management takes time and significant long-term effort on both sides of the "transaction" (change-makers and recipients). Being able to interpret when the change program has truly come to an end requires a thorough understanding of the situation and organizational atmosphere. It is only by taking into account all of these points that effective leadership in organizational change management can arise.

This post is part two of a dissertation I have worked on this year (with the precious help of my supervisor) on Effective Leadership and Organizational Change Management. To check out part 1, click here.

If you find this post of any value, consider signing up for our weekly newsletter around the deep life, deep work, Notion, and much more here.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Al-Haddad, S., & Kotnour, T. (2015). Integrating the organizational change literature: A model for successful change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(2), 234–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2013-0215

Anand, N., & Barsoux, J.-L. (2017, November 1). What Everyone Gets Wrong About Change Management. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/11/what-everyone-gets-wrong-about-change-management

Appelbaum, S., Habashy, S., Malo, J.-L., & Shafiq, H. (2012). Back to the future: Revisiting Kotter’s 1996 change model. Journal of Management Development, 31, 764–782. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711211253231

Ashkenas, R. (2013, April 16). Change Management Needs to Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/04/change-management-needs-to-cha

Bailey, C., & Madden, A. (2017). Time reclaimed: Temporality and the experience of meaningful work. Work, Employment and Society, 31(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017015604100

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2008). Academic Entrepreneurs: Organizational Change at the Individual Level. Organ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0295

Bozak, M. G. (2003). Using Lewin’s Force Field Analysis in Implementing a Nursing Information System. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 21(2), 80–85.

Bridgman, T., & Bell, E. (2016). Seeing and Being Seen as a Management Learning and Education Scholar: Rejoinder to “Identifying Research Topic Development in Business and Management Education Research Using Legitimation Code Theory.” Journal of Management Education, 40(6), 692–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916662103

Brisson‐Banks, C. V. (2010). Managing change and transitions: A comparison of different models and their commonalities. Library Management, 31(4/5), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435121011046317

Cannon, W. B. (1987). The James-Lange theory of emotions: A critical examination and an alternative theory. By Walter B. Cannon, 1927. The American Journal of Psychology, 100(3–4), 567–586.

Chesky, B. (2020). A Letter to Hosts. https://news.airbnb.com/a-letter-to-hosts/

Chesky, B. (2020). Airbnb’s Brian Chesky: “Crisis is pushing us back to our roots.” https://open.spotify.com/episode/5nPkARYaHjH6z9OhXDRcsp

Chesky, B. (2020, May 5). A Message from Co-Founder and CEO Brian Chesky. Airbnb Newsroom. https://news.airbnb.com/a-message-from-co-founder-and-ceo-brian-chesky/

Chesky, B. (2021). Airbnb’s Brian Chesky: “We died and were reborn.” https://open.spotify.com/episode/7kVN1rNawZy6rqVNEt7moy

Clayton, S. J. (2021, January 11). An Agile Approach to Change Management. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/01/an-agile-approach-to-change-management

Eisenstat, R., Spector, B., & Beer, M. (1990, November 1). Why Change Programs Don’t Produce Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1990/11/why-change-programs-dont-produce-change

Ford, J., Ford, L., & D’Amelio, A. (2008). Resistance to Change: The Rest of the Story. Academy of Management Review, 33, 362–377. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2008.31193235

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Boston: Beacon Press. http://archive.org/details/manssearchformea00vikt

Franklin, N. Z. H., Joshua. (2020, December 10). Airbnb valuation surges past $100 billion in biggest U.S. IPO of 2020. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/airbnb-ipo-idUSKBN28K261

Garvin, D. A., & Roberto, M. (2005, February 1). Change Through Persuasion. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2005/02/change-through-persuasion

Graetz, F., & Smith, A. C. T. (2010, June). Managing Organizational Change: A Philosophies of Change Approach. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697011003795602

Grant, A., & Kahneman, D. (2021). WorkLife with Adam Grant. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/episode/2ECDE4iEE8m9matZ7Pl8ni

Hamel, G., & Zanini, M. (2014, October 1). Build a change platform, not a change program | McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/build-a-change-platform-not-a-change-program

Isaacson, W. (2011). Steve Jobs. Simon and Schuster.

Jacobs, G., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Christe-Zeyse, J. (2013). A theoretical framework of organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26, 772–792. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-09-2012-0137

Rosenthal, R., Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev 3, 16–20 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02322211

Kahneman, D. (2011, October 19). Don’t Blink! The Hazards of Confidence. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/23/magazine/dont-blink-the-hazards-of-confidence.html

Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, Fast and Slow (1st edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.193

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. (2001, November 1). The Real Reason People Won’t Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2001/11/the-real-reason-people-wont-change

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2003, April 1). Tipping Point Leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2003/04/tipping-point-leadership

Klein, S. M. (1996). A management communication strategy for change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 9(2), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819610113720

Kotter, J. P. (1995, May 1). Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2

Kotter, J. P., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2008, July 1). Choosing Strategies for Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2008/07/choosing-strategies-for-change

Langer, E. J. (1975). The illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(2), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.32.2.311

Lawrence, P. R. (1969, January 1). How to Deal With Resistance to Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1969/01/how-to-deal-with-resistance-to-change

Lawson, E., & Price, C. (2003). The psychology of change management | McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/the-psychology-of-change-management

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concept, Method and Reality in Social Science; Social Equilibria and Social Change. Human Relations, 1(1), 5–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872674700100103

Madden, C. B. and A. (n.d.). What Makes Work Meaningful—Or Meaningless. MIT Sloan Management Review. Retrieved March 27, 2021, from https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/what-makes-work-meaningful-or-meaningless/

Merton, R. K. (1948). The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy. The Antioch Review, 8(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/4609267

Miller, D. T., & Ross, M. (1975). Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin, 82(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076486

Moran, J. W., & Brightman, B. K. (2000). Leading organizational change. Journal of Workplace Learning, 12(2), 9.

Natálio, J. (2019). Exploring the relationship between personality and cognitive bias to enhance user performance in adaptive HCI.

Nohria, N., & Beer, M. (2000, May 1). Cracking the Code of Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2000/05/cracking-the-code-of-change

Parmar, B., Freeman, R., Harrison, J., Purnell, A., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. The Academy of Management Annals, 3, 403–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2010.495581

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (2012). The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. University of Chicago Press.

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. (2019). Organizational Behavior. Pearson.

Roosevelt, T. (2006). An Autobiography. Echo Library.

Ryan, S. (2016, November 25). How Loss Aversion and Conformity Threaten Organizational Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/11/how-loss-aversion-and-conformity-threaten-organizational-change

Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations. Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.

Shepperd, J., Malone, W., & Sweeny, K. (2008). Exploring Causes of the Self-serving Bias: The Self-serving Bias. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 895–908. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00078.x

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. Penguin.

Sirkin, H. L., Keenan, P., & Jackson, A. (2005, October 1). The Hard Side of Change Management. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2005/10/the-hard-side-of-change-management

Snyder, M. L., Stephan, W. G., & Rosenfield, D. (1976). Egotism and attribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33(4), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.33.4.435

Todnem, R. (n.d.). Organisational Change Management: A Critical Review. 12.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Voltaire. (1759). Candide | Introduction & Summary. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 18, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Candide-by-Voltaire

Zhexembayeva, N. (2020, June 9). 3 Things You’re Getting Wrong About Organizational Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/06/3-things-youre-getting-wrong-about-organizational-change