Productivity: Doing More of the Right Things

Being a conscientious person, at a certain point in life you felt the need to maximize control over your existence and exploit time in the most 'productive' way, whatever that means. You felt an intrinsic drive to organize your life in an orderly manner and accomplish more, especially at work, because more means better, which means higher position in the social hierarchy, which implies more money to be earned. And, while thinking about it, you figured out that in order to become a more productive individual you needed to hustle, work hard, for long hours, even at night if necessary, because that would eventually, at some indefinite point, lead to the sought-after 'success', the climb in the societal hierarchy, the money, the attention, the 'power'.

You are all set mentally, so you begin to dive into the productivity world on the internet: many experts recommending the 10 best ways to get more done in a day, the innumerable forums focused on productivity, the articles explaining how using a certain productivity tool can change your life. And then the YouTube algorithm does the rest of the job, throwing at you any possible video confirming your belief in the productivity rush, with the confirmation bias partying in the process. Your motivation is high, and you begin to take action and fill up your calendar with everything possible that likely will make you earn more money.

After some time, you begin to question what you are doing, as if a dim stream of consciousness had arisen in you, urging you to step back, look at where you are, and trying to understand more about the why, the purpose, the intention. And the sudden appearance of consciousness also questions how worthy it is to be more productive, to mindlessly go through the most amount of work possible, and if that is a fulfilling way of conducting life.

It is a turning point. You convince yourself to start to dig deeper into the meaning of productivity, to try and find a more sustainable way of living where what you do is not merely dependent on making more money, but also accounts for passions, interests, expanding yourself as a human being, bringing some usefulness to people around you and society at large.

You tell yourself you should try to embrace life to its fullness, but then your mammoth starts to play the denial game: 'are you sure about that? Don't you really want that amazing amount of money that you would have if you were as productive as possible for the longest amount of time possible? Come on. Just some more time. You need some more time to be productive, to try to optimize every single area of your life before taking a break and focusing on what's essential. But for now you should keep going. Come on. '

Productivity is not doing as much as possible, mindlessly (or is it?)

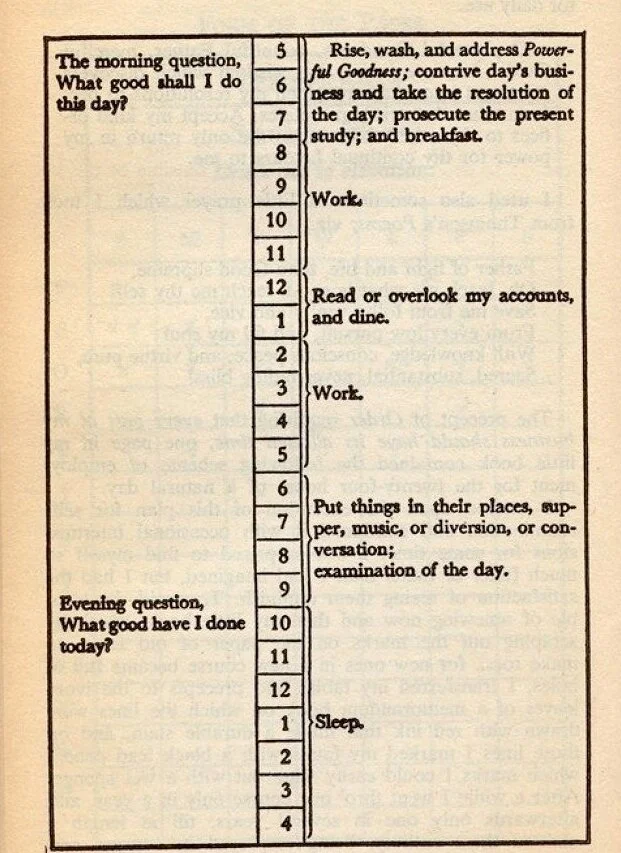

Benjamin Franklin's "To Do" List. Source: dailydot.com

The concept of Productivity was first invented in the 19th century, and it was merely related and applied to the economic environment. Productivity as a measure of output per worker, or output in general, applied especially in agriculture at the beginning.

As the time went by, however, Productivity expanded to the corporate world, but most importantly it entered the personal sphere of our lives, with the purpose being tied down to getting as much done as possible in a certain amount of time (per day, for instance). Which means that Productivity per se is an equation equal to output / time.

The productivity industry nowadays has become huge and goal-oriented. But new definitions and ways of 'being productive' are being explored.

A definition of productivity by Ali Abdaal recites: 'Productivity is doing the right things efficiently. It encompasses the principles, tactics and tools that help us manage our time, focus on what matters and execute consistently over the long term.' Ali Abdaal also offers a revised equation to describe productivity: Productivity= [(Useful Output) /(Time)] * f where f is the 'fun factor'. So, this definition adds 2 relevant components to the equation: output must be 'useful' (i.e. not procrastination-driven), and everything must be multiplied by the 'fun' factor, because if you can make getting things done 'fun', then you have reached a point in which the majority of the things you do feel like enjoyable activities rather than burdensome chores.

A popular 'subculture' in the productivity world is essentialism, a way of living invented by Greg McKeown and popularized in his book "Essentialism: the Disciplined Pursuit of Less". The fundamental idea behind this new age movement is that being productive means getting more of the right things done, where reflection, intentionality, and focusing only on what really matters are key pillars.

As these new views of productivity show, we have been shifting towards the belief that productivity encompasses much more than just 'getting stuff done'. Society is moving towards a more mindful approach to productivity, in which the 'people' factor is taken into account as well. By people factor I mean the fact that we are human and that our lives are likely not made to be dedicated completely to work and doing things just for the sake of making more money. Which is related to the rise in the feeling that work-life balance matters (but this is out of the scope of this article).

So, we have moved from a mindset of getting as much as possible done, no matter what, to a more balanced, intentional, mindful way of facing productivity and tasks in general. Being productive has taken a whole new definition: focusing on what is really important at a certain moment in time, intentionally and mindfully. Which also implies that taking a nap or spending some time 'doing nothing' is definitely ‘being productive’, if it is what you value and intend to do at that moment.

Some Fundamental Laws of Productivity

Parkinson's Law: work expands to fill the time that we allocate to it.

Parkinson's law takes the name from its inventor, Northcote Parkinson, a British historian who, in 1955, published an essay on the Economist observing that the time it took for the British Civil Service to conclude its projects would always expand based on the time planned.

If something must be done next week, it will be done next week. If something must be done in a year, it will be done in a year. Parkinson's law is not a rule rationalizing the use of very short and unreasonable deadlines for big projects. Rather, it is a useful tool to bring perspective and awareness to the real time needed to conclude a certain work.

A valuable question to ask yourself in order to apply Parkinson's law would be: "What would it look like if you finished that book you are writing in 6 months instead of 1 year?" Often times, as a matter of fact, projects can be concluded in a shorter time than planned, if you really focus on the essential tasks to do (the 20% of the things that bring the 80% of the results).

Pareto Principle (80/20 rule): 80% of the results come from 20% of the effort.

The Pareto principle could also be stated as "80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes". This law of productivity (which can be applied universally) was first noticed by Vilfredo Pareto in 1896, when the Italian economist concluded that roughly 80% of the land was owned by 20% of the population in Italy.

In productivity, the Pareto principle can be implemented by spending the most amount of time on those activities and tasks that generate the highest return, i.e. the 20% that bring the 80% of the results. So, the first step in the application of this law is to identify which are those activities that bring the most value.

The 2 minute rule: "if a task takes less than 2 minutes to get done, do it now".

This law comes from David Allen's bestseller "Getting Things Done". The 2 minute rule can also be applied to habit-building, as James Clear advocates. By making sure that it takes 2 minutes or less to get ready for an activity (e.g. working out in the morning by having your workout shoes within easy reach in the room you are), you build momentum, which helps you overcome that initial resistance towards starting and significantly increases the chances that you keep going once you are all set.

The same applies (in reverse) to "unlearning" a bad habit. By making sure that it takes more than 2 minutes for you to even start the bad habit, you create friction and decrease the likelihood that you actually begin. For example, if you want to stop playing videogames because you think this activity prevents you from doing what you need to do, an effective tactic could be to hide the joystick in a drawer which is in the farthest room in your house and maybe lock the drawer and put the key in another part of the house which is distant from the place where the videogame console and your workspace is.

Here are what I believe to be valuable resources to dive deeper on productivity:

Essentialism by Greg Mckeown (Skillshare Course)