The Practice and Science of Abs Training

Training abs is sometimes believed to be the end-all-be-all component of losing fat. A visible rectus abdominis is perceived, in society at large, as the ultimate sign of a healthy, fit human being. Often paired with this belief there is the notion that "abs are made in the kitchen", which is a saying one can hear from some people in the fitness scene. Although these thoughts are rooted in some truth, they seem vague and too generic to truly understand the practice and science of abdominal training. Having visible, blocky abs is a by-product of a low body fat percentage, which is manufactured in a harmonious mix between proper nutritional regimen (for some people it is merely necessary to not be in a caloric surplus) for an extended period of time and training. As a consequence, to begin with, we need to be very aware that only working the core muscles (of which the abs are just a part of) is, generally speaking, not sufficient in order to elicit the best results in uncovering the abs. Nutrition plays a pivotal role. We can think of training the abs as laying the building blocks for muscle development, on top of which we need to add appropriate nutrition (based on our current state) in order to make the abs muscles pop out. This is a very relevant mental model to have when it comes to abs development, because spot fat reduction does not seem to exist, as per current scientific evidence (Kostek et. al, 2007), although new contrasting findings have been arising in the scientific literature. One thing is certain, however: the energy balance principle is an undeniable process of physics. By training the abs we can develop the muscle mass in that area of the body, like we do with every other muscle group. However, because of the stubborn nature of the fat accumulated in the abdominal area, having visible abs requires getting rid of the layer of fat (in those athletes with relatively high bodyfat - >15-16% but depending on one's genetics). With that being said, being very shredded does not necessarily correspond to being and feeling healthy. As a matter of fact, getting to very low percentages of body fat (<8-10%) is an endeavor which calls for persistent discipline and some nutritional restrictions, which definitely act as stressors on the body and mind (Moraes et. al, 2018).

This article dives into the science and practice of abdominals training, hence without accounting for the nutrition aspect of a holistic approach to health and fitness. We will kick off the journey by analyzing the anatomy of the rectus abdominis and nearby muscles.

Anatomy of the Abs

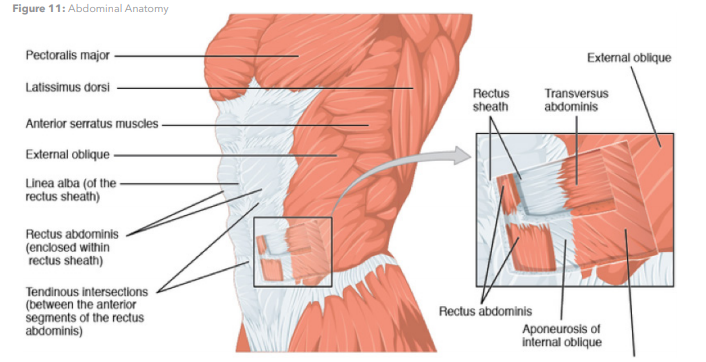

Source: Openstax

The muscles comprising the abdominal area are only a part of the core. There is a difference between the two, although we may sometimes confuse them. We will look at the differences between the rectus abdominis and the core later in the article. For now, let's focus on the anatomy of the main muscles composing the abdominal area. These are the most relevant ones in the context of abs training (because we can target them with specific movement patterns): the rectus abdominis, external and internal obliques, transversus abdominis, serratus anterior. Different movement patterns stimulate these areas of the abs to a varying degree. The main job of the rectus abdominis is to flex the spine, rotate the torso, and prevent spinal extension (resist lower back from arching inward excessively).

Movement Patterns Targeting the Abs

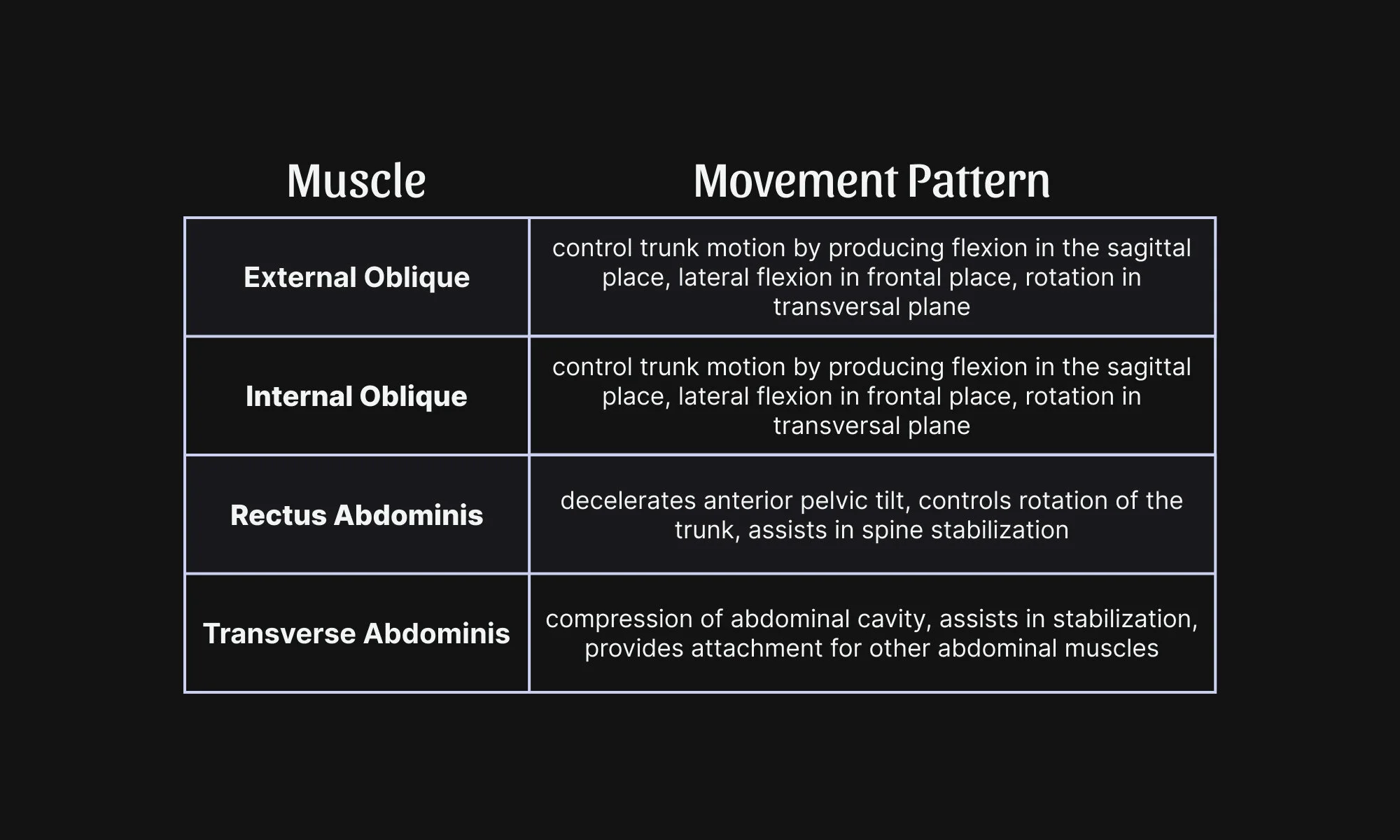

Source: Openstax

Every muscle group has some movement patterns associated to it eliciting the greatest activation. The main function of the abs is to stabilize the spine and make us stand upright. So, first and foremost, the abs (as part of the core) act as stabilizers. Having strong abs does not merely translate to lower risk of injury in the spine, but it also transfers very significantly to properly performing exercises at the gym and in sports in general. When it comes to resistance training movements, a solid core sustains the rest of the body throughout the duration of them, by stabilizing the spine during the execution (e.g. stable core in a squat). In dynamic sports such as soccer, the abs assist the wide variety of rapid movement patterns occurring while playing (e.g. jumping and landing with sufficient stability in a head kick, or balancing the body in the transversal plane when changing direction forcefully).

In addition, in the sagittal plane, the abs are responsible for spinal flexion (e.g. crunch) and preventing excessive spinal extension (i.e. preventing the spine to arch inward excessively). In the transversal plane of movement, the role of the abs is to rotate the torso (e.g. russian twists). Also lateral flexion is part of the main functions of the muscles included in the abs (frontal plane of motion). In addition to those, it is well worth pointing out that the role of the abs is also to prevent rotation and spine extension from happening (anti-rotation and anti-extension). As a consequence of the numerous patterns the rectus abdominis is involved in, a comprehensive abs training routine takes them into account by including exercises working in different planes. By doing so, we can develop a stronger, more functional rectus abdominis and, consequently, core. The abs are only a part of what is known as the core area of the body.

The Difference Between Abs and Core

As dr. Stuart McGill points out (2010), the core is “composed of the lumbar spine, the muscles of the abdominal wall, the back extensors and quadratus lomborum. Also included are the multijoint muscles, namely, latissimus dorsi and psoas that pass through the core linking it to the pelvis, legs, shoulders and arms” (McGill, 2010). The abdominal wall is only one component of the core of our body. The key function of the core is to create stability. The core is what allows us to walk and stand upright. Its stabilizer function makes it pivotal in injury prevention during training, as well as the source of tension during the Valsalva maneuver, which is often used in lifting in order to increase stability and tightness of the body during heavy exercises. A complete training program does not neglect the relevance of exercises targeting the lumbar spine, glutes, and back extensors.

Expectations from Direct Abs and Core Training

At this point we know that training the abs does not make fat go away all at once. Developing strong core and abs, however, does make the difference in increasing a sensation of stability and power in everyday life and training alike. In addition to this benefit, direct core training also develops the muscle mass of the area of the body, if paired with an appropriate nutrition regimen based on our current objectives. Building abs requires consistency and deliberate practice. So, here is a list of possible expectations to have in the field of core and abdominal training:

Directly training the abs does not elicit spot fat loss reduction. A calorie deficit is needed in order for fat loss to occur holistically in the body. Direct abs training does, nonetheless, develop muscle mass within the worked region of the body, which can enhance the aesthetic look of them in the short run (but highly dependent on body fat percentage), eliciting the "pump" sensation. Consistent core training has an effect on stability and muscle development in the medium-long run.

Direct core training carries over resistance training exercises such as the Squat, Overhead Press, Deadlift on account of the stability-enhancing component of the core muscles, which is crucial in the performance of resistance training movements (Szafraniec et al., 2020).

When it comes to progressing core exercises, dr. McGill (2010) provides the following framework of reference:

Corrective and therapeutic exercise to enhance stability and mobility

Groove appropriate motor patterns

Build whole-body and joint stability

Increase strength-endurance

Build strength

Develop speed, power and agility

A Complete Abs and Core Training Routine

By clicking on the button below you can take a look at an example of a complete abs training routine, including a possible frequency and some rationale behind the movements included (although let's not forget that we humans are great at rationalizing things even when unnecessary. Working out the core muscles is still better than not doing it at all, no matter the rationalization behind it).

If you find this article valuable, consider signing up to the Weekly Reflection here: a once-a-week newsletter around psychology, existence, and anything essential in life.

RESOURCES

Science and Development of Muscle Hypertrophy | Brad Schoenfeld

Exercise Anatomy: Abs Workout | Pietro Boselli

The Perfect Abs Workout | Athlean X

How to Get Six Pack Abs: Abs Training Science Explained | Jeff Nippard

How to Build a Better Core and Six Pack Abs | Jeff Nippard

Beginner's Guide to Six Pack Abs | CalisthenicMovement

ABS 101 | AthleanX

Functional Anatomy Series: the Abdominals | ACE Prosource

New Science: Spot Reduction is Not a Myth | Menno Henselmans