The Social Need to Conform

““It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.””

Clinical psychologist and psychology professor dr. Jordan B. Peterson often reminds us, in his lectures, how easy and comfortable it is for us to condemn evil actions carried out throughout history by human beings (e.g. Nazis). But are we sure we would not have done the same, if we found ourselves in the same position of those seemingly evil people? Taking into account the incredible amount of social pressure, manipulation, censorship, climate of conformity that was around?

Being aware of history and the consequences of actions driven by the worst nature of human beings is a crucial step towards not repeating them and paying close attention to what we do. Finding ourselves in high pressure situations that may lead us to act against our principles merely for the sake of feeling accepted is a common occurrence in life. Take a look at this study (Milgram, 1963).

Cognitive psychology refers to this as the survivorship bias: it is easy to condemn some objectively negative decisions and actions other human beings did in the past, while in the comfortable sofa in our warm house. But what would happen if we found ourselves in high-social-pressure situations? Our vision may become completely foggy, and reality as we see it blurred and distorted. Actually, I would argue that it is a rather common occurrence in life; to come to terms with decisions or requests we do not feel ethically bound with. Which we would love to reject but feel like cannot due to the many factors at play (social, psychological, practical).

Trying to explain the concept of conformity is not a straightforward task. The individual and the group are the two key players when it comes to mapping out conformity. The group is the set of people sharing common values, goals, interests and aiming toward the same direction. Crucially enough, every group is composed of individuals, with their flawed minds, varied personality traits and attitudes, relatively differing ideas and habits. In our daily life, normally, we are part of numerous groups, whether it be at work (formal or informal groups), in our social life, or merely considering our family, which is still a group of people balancing collective and individual needs.

The reasons for which we gather in groups are likely to be found in our innate evolutionary aspects of being social primates. We organize in societies and subgroups, often characterized by some sort of hierarchical structure, even if unspoken or not acknowledged. And we do so because this is an inherent element of the human condition and evolution of the species. Conformity, hence, refers to a group situation in which we feel the urge to respect the standards and norms (whether explicit or implicit) of a group. The degree of conformity can be imagined as a spectrum, in which a lot of individual variables determine our need or tendency to conform (e.g. personality traits, social hierarchy, status, characteristics of the situation).

Regardless of personality traits and characteristics of people, social identity theory can help us figure out why we conform: we derive identity from our reference groups. Our reference groups are all those groups which we regard as important and are part of or hope to belong to (Organizational Behavior, Robbins & Judge).

This theory raises two pivotal implications. First, not necessarily every group we are part of is a reference group for us (e.g. we may feel detached from a formal group we belong to at work). Second, groups have a deeper meaning for us than what we can see on the surface: we tie our self worth and identity to the groups we consider important.

The identification aspect of group dynamics creates an additional relevant point to bring up: ingroup favoritism. This is a concept according to which we tend to favor our groups' accomplishments and qualities, while disregarding outgroups' characteristics (i.e. any group which is different from ours - e.g. radical republicans vs. radical democrats in American politics).

Favoritism stems from the fact that we identify with our groups. Consequently, we attempt to validate our beliefs and values comparing our group to outgroups and finding confirming evidence to support our choice of identification with a certain group (confirmation bias). This, in turn, raises our perception of the position our groups (and hence we) occupy in the social hierarchy (status). A self-esteem booster.

There are two additional motives that can be identified in the analysis of conformity and group identification: social and peer pressure. In the wide majority of areas of life (including groups), we are organized in some resemblance of social hierarchies, whether we like it or not, in which some individuals are perceived to rank higher and others lower, in a pyramid-like fashion. Now, while a strong argument against the benefits of playing the status game in life can be made, we do it all the time, although to varying degrees of intensity. The book 'The Elephant in the Brain' is a good read on the hidden motives in everyday life (my summary here).

Status games are short term and finite. They concern those decisions in life that we make (whether consciously or not) in order to climb the social hierarchy, get more power, authority, possibly money, or respect. The ego draws a lot of short term energy from status games. Our true identity, however, may suffer in the long term.

Now let's go back to social and peer pressure dynamics in conformity. Especially when in group situations, and particularly if we do not rank high enough in the social hierarchy of the groups (e.g. newcomers in a company team), we tend to want to be accepted by the members of the group. This is much more marked if you score high in trait agreeableness (Big Five Framework). This tendency may have something to do with our evolutionary reasons of being social animals who value and yearn for connections and sharing for survival. But it also has some practical, short-term reasons.

If you have just been hired by an organization, for example, and you would like to succeed at your job and tasks, you better behave in a socially-acceptable manner. This means being high-integrity, meeting deadlines, doing things with the appropriate amount of effort and precision. And it also means being aware of your position in the group's social hierarchy, and being ok with it, knowing that your position is constantly varying based on how you behave, communicate, perform. Life is a series of games, and many times you want to be playing those games respecting the rules (without blindly conforming to them however), unless you know better.

Peer pressure, conformity, fear of not being accepted are some of the human elements that the very famous studies by Asch and Milgram raised awareness on. Both of them took place during the last century (XXth) and have been crucial to the understanding of conformity in human beings.

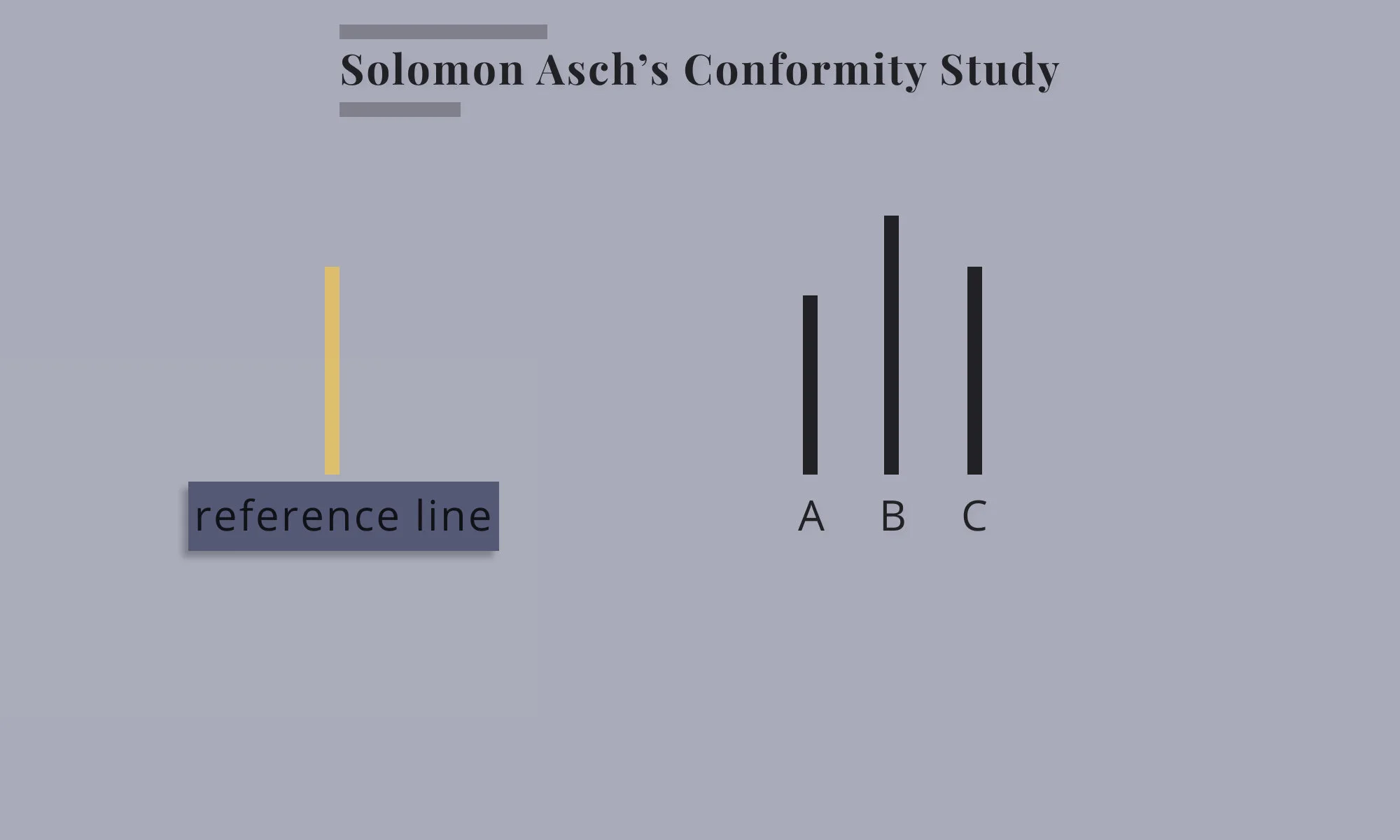

Picture this (Asch conformity study): you are told you will be evaluated on the capacity to assess the length of vertical lines besides each other and state which lines are of the same length (e.g. see picture below).

You enter a small classroom in which there is a group of other people, maybe 5, or 10. You believe that also these individuals are subjects of the experiment. In the classroom, there is also the experimenter. He projects images on a whiteboard and asks each person sat in the classroom to state which line is of the same length of the one on the left. You are asked to give your opinion last (and you are not aware that you are the only actual participant of the experiment). A seemingly simple task. Let's see what the experiment looked like in this old video. The main finding of the Asch conformity study was that the majority of participants provided the same answer to his/her peers, even if obviously wrong, on account of the perceived pressure to conform.

A second iconic social experiment on conformity and social pressure was set up by Milgram et al.

The human nature cannot be changed, and the yearning to conform is an inherent part of us. We are social animals who want to be accepted by other people and feel a sense of belonging.

We can, nonetheless, be aware of the fact that conformity stemming just from social pressure or fear of not being accepted is a natural mechanism at play in group settings.

Being aware of this can provide us with the possibility of recognizing what our values are, disagreeing if we think this is the correct thing to do. Or simply mindfully playing the games we inevitably engage with during our existence.

In this manner, we may choose whether to conform or not, not completely driven by social circumstances but by our own principles and decisions. Not seeking status or power, but letting life unfold for what it is, conscious of the social nature of the human experience.

““A contrarian isn’t one who always objects—that’s a conformist of a different sort. A contrarian reasons independently from the ground up and resists pressure to conform.””

I write a weekly newsletter. If you find this post valuable, consider signing up to it (maybe after having scanned through some past issues) here.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

What Working with psychopaths taught me about leadership | Ted Talk

Organizational Behavior | Robbins & Judge

Asch Conformity Experiment | Khan Academy

Milgram Study on Obedience | Khan Academy

On Stopping to Care About What Others Think of Us (In Depth) | Pietro Boselli Phd

Conformity to the opinions of other people lasts for no more than 3 days

SIMILAR POSTS