Learning is More Effective with These Techniques

Learning is, whether we like it or not, an inevitable part of our existence. We live to learn. We learn by living, experiencing stuff, and also watching other people. In the more traditional sense of the word, formal learning happens for the most part during the first 20 to 30 years of our life. This is the type of learning that is somehow required by society, and whose main purpose is to provide us with a "certificate" of trustworthiness. As a matter of fact, when it comes to studying in school and universities, what we are being "tested" on does not concern very much theoretical concepts and notions (although this is certainly what it looks like on the surface—and it has its importance too), but a more "hidden" and socially-valuable skill: being civilized individuals who can live harmoniously in the society (once out of school), and who can abide by their duties in the workplace. Going to school, getting a high school diploma, and university degrees, are all ways of signaling to prospective employers and the society at large that we are proper citizens, that we can be trusted upon, and that we hold ourselves accountable. This is not to discredit having knowledge in a field. Rather, I find this to be an interesting, hidden motive which is not much talked about, despite its relevance.

The theory of studying as a means of signaling our societal fitness is an economic theory whose author (Michael Spence) has been awarded the Nobel Prize in the early 2000s. For more about that, here is his full argument about signaling.

Nevertheless, pretty much all of us are aware of the existence of two main categories of people out there: those who do not enjoy learning for the sake of learning, and those people who feel intrinsically motivated to improve themselves and enrich their cultural baggage. Actually, this is more of a continuum, of which the categories I have described above are just the two extremes.

This characteristic which can be found in individuals seems to be related, to some degree, to disposing of an intrinsic motivation to learn new things, versus being extrinsically motivated. When we are intrinsically motivated to do something, the urge and genuine interest comes from within. We do not need external forces or motivations to push us forward. Every one of us, in at least one area of life, usually feels a deep, internal drive to take part in a specific activity, whether it be improving oneself, doing sport, writing, reading, etc. Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, relies on external objectives, milestones, or, more broadly motivation, to do something. This is often the case for work: many people do their job just because they need money to survive(as well as a high-enough place in the societal hierarchy).

This TED Talk on intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation by dr. Boselli is a good watch.

In any case, whether we are inherently leaning towards learning for the sake of learning, or we force ourselves to learn because of external forces requiring us to update our curriculum vitae, most of us, especially in our adult life, have a limited amount of time to dedicate to the activity of studying and absorbing new ideas or skills.

And, like most habits, giving structure to learning/studying can enhance outcomes significantly. What I mean by this is that the only thing under our control when it comes to doing an activity, or practicing a task, or just studying, is the time we allocate to that activity, and the structure we give to it. Relying on motivation to do something is probably not a great medium-to-long-term strategy, at least for the majority of people.

We have control, to a great extent, over how we spend our time, and the quality of the work/learning we do during that time.

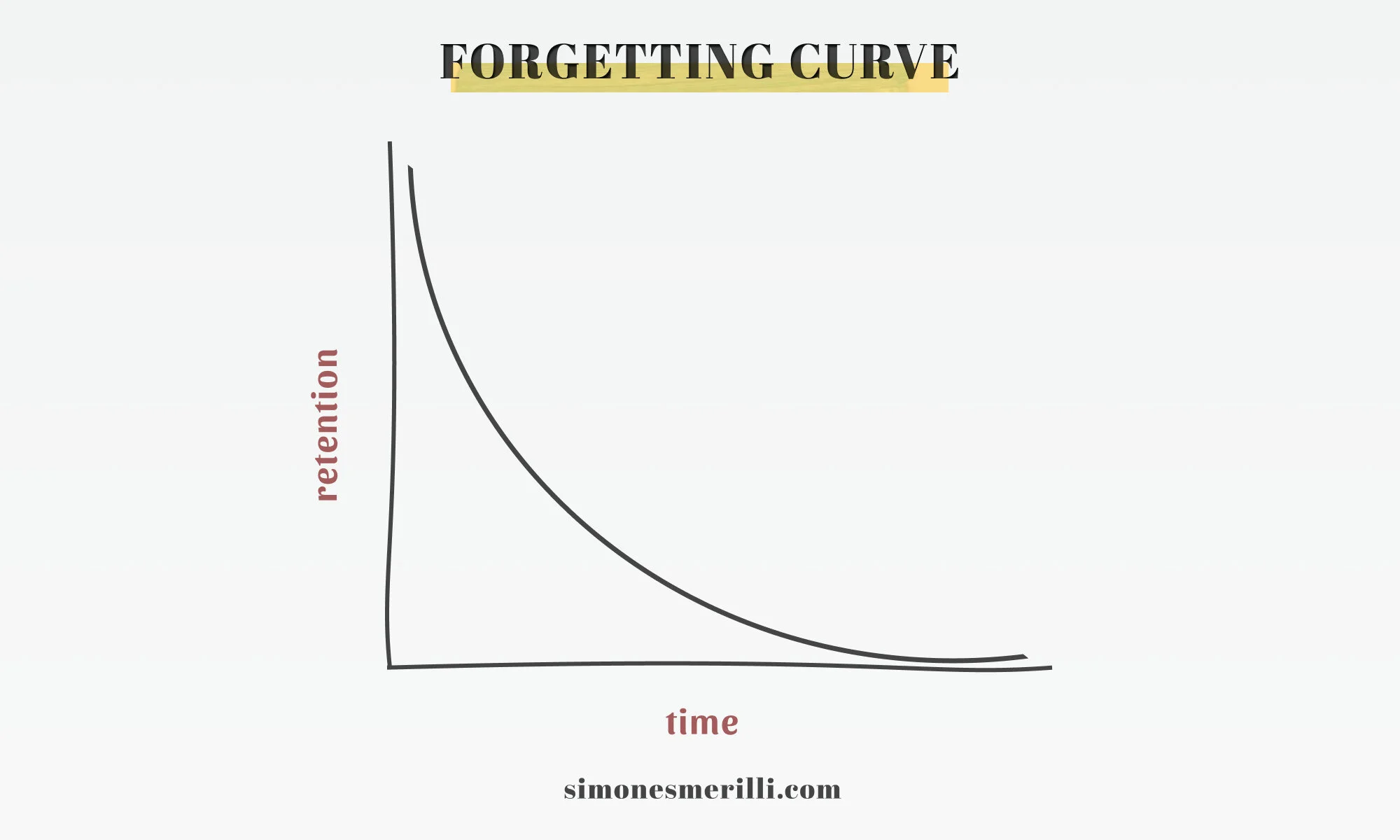

And while keeping a personal knowledge management system is a great habit (in my opinion), it is likely not enough to remember things. Indeed, one of the biggest hurdles when it comes to internalizing new knowledge lies in the fact that we forget stuff very rapidly. This is fairly clear for students (at least for me). We tend to cram studying into a short period of time before the date of the exam, to then do well at it, but forget pretty much everything after just a couple of weeks. And, if we do not revise the content, it just ends up in the most remote part of our brain, to then leave it at some point.

The Forgetting Curve

This is what German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus studied and researched: the forgetting curve. Memory retention declines in time, when there is no effortful attempt to retain it. He also defined a key antidote to the forgetting curve: active recall (and consequently spaced repetition).

Active recall and spaced repetition are two of the most evidence-based approaches to learning for the long term. Spaced repetition, in particular, is a technique especially designed to combat the effect of the forgetting curve. Ebbinghaus laid out the foundations for the development of spaced repetition by first bringing awareness on the existence of the forgetting curve.

Active recall and spaced repetition can be game-changing learning methods, if incorporated strategically into our studying or learning routines. Let's understand better what they are.

Active recall refers to the deliberate practice of learning new knowledge by testing ourselves on it, rather than passively trying to absorb it. The most renowned method to apply active recall uses flash cards in order to test our understanding of a topic, even if there are numerous other great techniques to implement active recall, such as the Cornell Note Taking System.

Spaced repetition, which is usually complementary to active recall, is a strategy according to which the rate at which memory is lost declines over time, as we retrieve the information at incrementally spaced intervals, ideally up to a point at which the forgetting curve almost flattens.

Implementing active recall and spaced repetition requires more effort and intention compared to just going through the motions and reading/highlighting. But the potential long term outcome might be worth the extra effort in the present moment, especially if one of your main problems in learning is the forgetting curve. Here is a post on how I use Notion to apply active recall and spaced repetition to study for university. Also, Ali Abdaal is a great resource to learn about study methods and these techniques.

3 Famous Study Principles and Methods

Although introducing active recall and spaced repetition into your learning system may feel rather daunting (it certainly did for me), a clear structure and method to them is probably all that is needed. So, here are some of the most renowned principles and time-management methods to make the process of learning more fun and rational.

The Pomodoro Technique 🍅

Very popular in the productivity world, the pomodoro technique first came to be in the 1980s, brought to consciousness by then university student Francesco Cirillo.

This is an interval-based time management method mostly applicable to doing activities that require high concentration. Its main aim being to overcome slumps and the unwillingness to focus on doing work/studying, it is based on four iterations of an interval: 25 minutes of work, followed by 5 minutes of break. At the end of the 4 iterations (totaling to 2 hours), a longer break is taken (usually 10 to 20 minutes).

The real power of the Pomodoro technique lies in its relatively short bursts of work (25 minutes), which seems to be a great hotspot for tricking the mind into starting to do the thing, because 'well it's just going to be 25 minutes'. This initial commitment, however, is more often than not the catalyst for momentum, and the flow state.

Parkinson's Law 📅

“Work expands to fill the time allocated to it.”

Parkinson's law takes the name from its inventor, Northcote Parkinson, a British historian who, in 1955, published an essay on the Economist observing that the time it took for the British Civil Service to conclude its projects would always expand based on the time planned.

This rule of thumb is very noticeable in students preparing for exams. The exam date represents a deadline, which is the defining characteristics of Parkinson's law, and many students procrastinate the process of studying as much as possible, to then end up cramming everything within the few days preceding the date of the test.

If we look at the relevance of spaced repetition and active recall in learning, piling up study material and trying to absorb a lot of information in a limited amount of time is not a long-term, healthy strategy for memory retention. It may be sufficient to let you pass the exam, but chances are almost everything will be completely forgotten after a couple of weeks.

Parkinson's law can help in beginning to work on the things that we need to do (or study). In particular, it can be taken advantage of through establishing self-imposed deadlines on projects and tasks that need to get done. This makes the process of starting more smooth, and can be beneficial when it comes to not end up doing all the work as the deadline approaches, by creating a sense of urgency to some degree. It is, however, tougher to take advantage of Parkinson's law when studying for exams, since exams dates are externally set. So, discipline and intrinsic motivation to learn and retain knowledge are more relevant in that case, I would argue.

"What would it look like if you finished that project X in 3 months instead of 6?"The 80-20 Rule (Pareto Principle)

“Roughly 80% of the knowledge in a field comes from the most fundamental 20% of the information.”

The Pareto principle could also be stated as "80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes". This mental model (which can be applied universally) was first brought to light by Vilfredo Pareto in 1896, when the Italian economist noticed that roughly 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population.

The 80/20 rule plays a crucial role in learning, due to the fact that it makes us aware of the general truth that there is a 20% of the contents we are learning that is worth 80% of the whole knowledge in the field. This helps with searching for this 20% of fundamental information, in order to focus more time on internalizing it.

Furthermore, the 80/20 rule is rather noticeable in academic settings in general: teachers, generally speaking, allocate more time on explaining a small set of key notions and concepts during lessons. If you can identify this selected 20% of the knowledge, you are one step closer to passing the exam with ease, as this 20% of the concepts will very likely yield 80% of the results in the final test.

““It’s much more important today to be able to become an expert in a brand-new field in nine to twelve months than to have studied the “right” thing a long time ago. You really care about having studied the foundations, so you’re not scared of any book. If you go to the library and there’s a book you cannot understand, you have to dig down and say, “What is the foundation required for me to learn this?” Foundations are super important. “”

Being mindful of these fundamental truths in learning is a first step towards mastering the skill of improving as a person, and doing so in an enjoyable way. As a matter of fact, applying these techniques and methods should probably not feel cumbersome or exhausting. Their role is to make the process of learning, or studying, more smooth, structured, and ultimately mindful.

By taking a more intentional approach to learning and disposing of an internal locus of control we can, steadily, move towards being the type of person who does not need to rely on external sources of motivation, but who can freely choose their own, unique destiny.