Everything You Need to Know About Training Volume

Workout volume is indisputably a key variable responsible for muscle hypertrophy. Using and manipulating it wisely in training programs can make the difference when it comes to optimizing results over the long run. This post is a complete overview of workout volume as far as muscle hypertrophy is concerned, and it takes into account the current scientific evidence on the topic, with links to resources at the end of the article.

Training volume is a fundamental variable that enhances muscle growth, and it has many nuances to dig into. In the last 3-4 years, I have been researching and exposing myself to a lot of science-based content about fitness and muscle hypertrophy in general, as well as applied the concepts I have learnt about the subject into my own training programs and training sessions.

So, I'll attempt to write about training volume in an in-depth manner, basing my statements on the current scientific evidence, which I'll link to at the end of the article (as well as in the body of the article when necessary). The way I'll try to treat the topic is through breaking it down into its key components, starting from the very definition of volume in resistance training.

Consequently, I have decided to divide this post into these parts (feel free to jump on what interests you by clicking on the links): we'll kick off by giving a clear definition of training volume, we'll then look at why training volume is such a relevant variable for muscle growth; thirdly, we'll understand what is the most optimal volume range (in terms of working sets) according to scientific evidence; finally, we'll get into some nuances of volume such as MEV, MRV, what the amount of volume depends on, and why a lot of volume is not enough by itself, before summarizing some crucial programming implications.

For some time, when I first began to attend the weight room, I was exposed to a mindset that has its foundations on lifting very heavy, pushing as hard as possible in every training session, annihilating the muscle worked, warm-up is not needed, etc. This approach to training was just implemented by me via analogy-based reasoning: whatever the "experienced" people say, it must be right.

However, with time going by and my interest in the subject of fitness and weight training growing stronger in me, I started to dig deeper into the topic, and I became aware of the fact that there's a scientific way to look at lifting weights and fitness in general.

This field is rather extensively studied in scientific literature, although mostly at beginner and intermediate stages of a lifter's career (what I mean is that most of the studies in the fitness world look at the effect of inputs on beginners and intermediate lifters). This realization has also made me understand that many nuances are part of the lifting world, and with volume being one of those nuances and a fundamental variable in workout design, this post will explore it, trying to reason from first principles.

What is Training Volume?

Volume can also be calculated as total amount of working sets per muscle group per week.

Training Volume is defined by the formula sets x reps x weight. So, volume is the amount of work performed in a training session (or week of training, or training program,...).

Volume and Intensity of Training are the two key variables (but not the only ones) at play in a training program. They are called variables because they can be manipulated based on the objective of the training plan. Generally speaking, there is an inverse relation between volume and intensity: the higher the volume employed, the lower the intensity (% of 1RM) implemented. This is because a high volume means a lot of load and fatigue for the muscles trained, which, if paired with very heavy weight relative to the 1RM of the trainee, can easily lead to overtraining in the medium term. Overtraining is the condition in which muscles cannot recover fully between training bouts due to the excessive amount of strain and the athlete feels exhausted, sore, and incapable to keep progressing in the workouts.

There is no unique way of calculating training volume, although the formula presented above is likely the most used. In fact, the amount of volume can also be computed by counting the working sets per muscle group of a certain program or session (this method of calculation is especially applied to bodybuilding, where weight per se does not play a crucial role). But more on this later in the article.

A key idea to be aware of when it comes to volume has to do with the fact that the amount of volume we can handle is supposed to increase as our lifting experience advances. As a consequence, advanced lifters (those with 5+ years of serious training experience) usually need more volume in their workouts because their muscles have grown and adapted over time and now need more training stimulus compared to beginners and intermediates.

Why Training Volume is a Key Variable for Muscle Growth

Volume and hypertrophy have a dose-response relationship, which means that the more volume is implemented in a workout program, the more muscle growth occurs. However, it is definitely the case that this does not apply indefinitely. More volume does not equal more muscle hypertrophy, infinitely. There is an upper threshold at which level more volume leads to diminishing returns, resulting in excessive fatigue, "junk volume”, and overtraining.

The reason for which volume is key to inducing muscle hypertrophy is to be found in the principle of progressive overload and muscular adaptation. Progressive overload is a principle of training according to which, in order for muscle growth to occur, there must be a progression in an athlete's ability to perform an exercise. That progression can take place in numerous ways, among which: increasing weight over time, increasing the sets performed of a certain exercise over time, improving the form of a certain exercise over time, or using a slower tempo of execution of a certain exercise with the same weight.

Progressive overload is necessary due to the muscular adaptation that takes place during our lifting journey. Indeed, as we keep performing the same exercises and movement patterns over and over again, our nervous systems and muscles become more efficient at doing them, hence adapting and needing more volume in order for muscle growth and maintenance to continue.

What is the Ideal Range of Volume?

When it comes to the ideal amount of volume to be employed in a training program in order to maximize muscle hypertrophy, there seem to be some landmarks and limits to respect in order to make the most out of our workouts without compromising recovery and performance. One of the most popular theories regarding the ideal set volume range per week per muscle group is one by Mike Israetel, Phd, also put forward and supported by James Krieger.

Dr. Isratel identifies an ideal set range that goes from a minimum of 10 sets per muscle group per week to a total of 20 to 25 sets per muscle per week. The maximum amount of volume varies depending on the experience of the lifter as well as the type of muscle group, with the "bigger" muscle groups usually needing more stimulus to grow (back, legs, chest), as well as to maintain, compared to smaller areas of our body such as the biceps and calves.

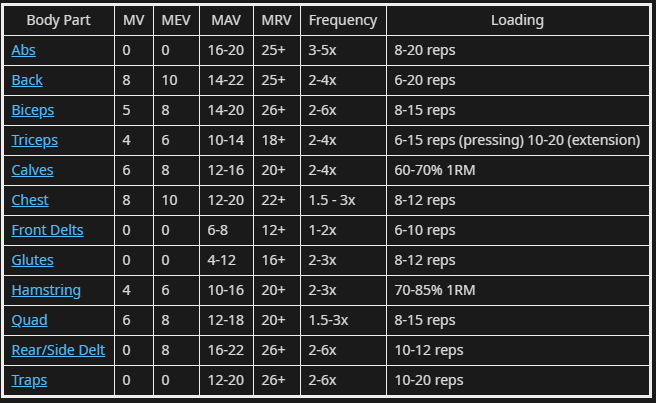

Source: Reddit

The table above gathers the volume recommendations by Dr. Israetel. Let's analyze the meaning of some of the terms in the first row of the table.

MV stands for Maintenance Volume.

This is the bare minimum amount of volume (number of sets) needed to maintain the muscle mass you already have. Here we need to note that the value of the MV varies based on the level of experience and the amount of muscle mass you have. In particular, if you have never trained, your MV will be 0 sets; whereas if you are an experienced lifter the MV will definitely be greater than 0, because muscle won't retain itself without at least some training. The good news is that the MV is generally low even if you are an advanced lifter.

MEV is the Minimum Effective Volume.

As dr. Israetel puts it: "This is the amount of training that actually grows your muscles: anything below this amount may only maintain them." The difference between the MEV and the MV grows larger as you become more experienced in your training journey.

MAV stands for Maximum Adaptive Volume.

This is the range of volume in which the most optimal muscle gains happen. The MAV, differently from the other landmarks, fluctuates greatly over time, as you go through mesocycles. The reason being that your muscles adapt to a certain amount of volume and load over time, which implies that you can handle more volume as the weeks go by, until you reach a point in which your MAV clashes with your MRV (maximum recoverable volume). And when that happens, you deload, to then restart the mesocycle of volume progression again and again.

MRV is the Maximum Recoverable Volume

i.e. the maximum amount of sets your body can handle per muscle group per week. Although training hard is fun and has its relevant place in lifting weights and training in general, excessive volume creates excessive fatigue, which prevents your body from recovering from training bouts, hence getting into overtraining and leading to diminishing returns (regression instead of progression in muscle hypertrophy).

The amount of set volume which is considered ideal for muscle growth is clear now, but what about the frequency of training?

The frequency of training corresponds to how often you train. Research shows that targeting each muscle group more than once per week (2 to 4) is ideal and much better compared to dedicating a whole session to one single muscle group. Higher frequency of training allows to spread out the volume for each muscle group among more than one workout each week.

This is optimal for one main reason:

Spreading the volume per muscle group among multiple sessions each week prevents us from doing junk volume. Junk volume is that ineffective and useless volume which takes place when you are very fatigued at some point in the middle of a long legs session and you still have 2 or 3 exercises before concluding it. These final sets are likely being performed poorly and not effectively owing to the high level of fatigue coming from the previous movements performed. So, training each muscle group more than once per week allows to prevent this from happening and, overall, can also enable to accumulate more volume, provided that it is spread among different sessions and that recovery is enough.

Training each muscle group two or more times per week makes training splits such as Full Body, Upper/Lower, Push Pull Leg or some variation of those ideal in practical application.

Programming Implications

When preparing a training program aimed at maximizing muscle hypertrophy, all this information on training volume must be taken into account, as volume is the most influential variable eliciting growth. So, to sum it up, here are some things to keep in mind when designing a workout program aimed at muscular hypertrophy:

A high frequency of training and a lower amount of volume per session per muscle group is suggested. Keep in mind that it is "better" to hit each muscle group more than once per week, spreading out the sets per muscle group on more than one session, which prevents junk volume from kicking in.

The MEV, MAV, MRV of trainees change based on the years of lifting experience, as well as genetics factors and other variables such as recovery and intensity of training.

The ideal range of sets per muscle group per week is anywhere between 10 and 25 working sets at a minimum of RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) 6-7 (4-3 reps in reserve). You usually want to begin a mesocycle with the lower end of the range to then increase volume over the microcycles until you reach the MRV and deload.

Do not stress to much about volume. Although it is the most relevant variable for creating hypertrophy, it is just one piece of a bigger puzzle, so you may not want to sacrifice effort just for the sake of theoretical implications. Training is a journey and it should likely not sacrifice fun just for the sake of data.

Training Volume is not everything that matters

Although volume plays a crucial role in producing, maintaining, or even decreasing muscle hypertrophy, it is just one variable in the grander scheme of things when it comes to fitness and training. It is certainly a key variable if your goal is to gain pure muscle mass. However, there are other inputs to keep in mind and apply in workouts: intensity of training and effort are among the most important. The former refers to the percentage of 1RM lifted (which is very relevant for powerlifting and weightlifting, disciplines in which lifting as heavy as possible is the main target), while the latter is the effort you put in each session, how hard you train and apply yourself. Training hard does not necessarily mean reaching failure on every lift and using bad form. It encompasses a whole mindset of training, where you are focused on feeling the muscles contract and elongate, you push yourself when you can and should, and you maintain concentration (but do not take it too seriously, hey).